Last November, Portland Public Schools (PPS) and the Portland Association of Teachers (PAT) waged one of the longest teacher strikes in recent American history, closing schools including classes, clubs and sub-varsity sports for over three weeks. The district then made $30 million in budget cuts in June, citing “investments in staff” as a cause behind the reductions.

PPS isn’t the only one saying there isn’t enough money in the system. School districts from all across Oregon have been fiercely demanding that legislators in Salem provide more support as they navigate ongoing financial challenges. Superintendents from Portland, Salem-Keizer, Bend-La Pine and Medford jointly posted a YouTube video declaring the situation a “crisis” in May.

Governor Tina Kotek has made a proposal to add $515 million to the State School Fund over the next three years, but Lincoln High School Principal Peyton Chapman is concerned that it won’t be enough.

“It won’t cover the increased costs of teacher salaries and facility needs,” Chapman said.

Chapman points to the socioeconomic barriers to accessing higher education and the skyrocketing demand for mental health services as examples of why robust funding for schools is essential.

“College tuition is going up, houselessness, mental health needs, all of those are really important and if we have solid education for everybody then I think we’ll prevent some of those problems,” Chapman said.

She also mentions that although Lincoln was able to retain most of its support staff and elective programs for now, it will only get tougher to preserve those amenities in the future if help doesn’t arrive soon.

“We’re not going to have as much flexibility,” Chapman said.

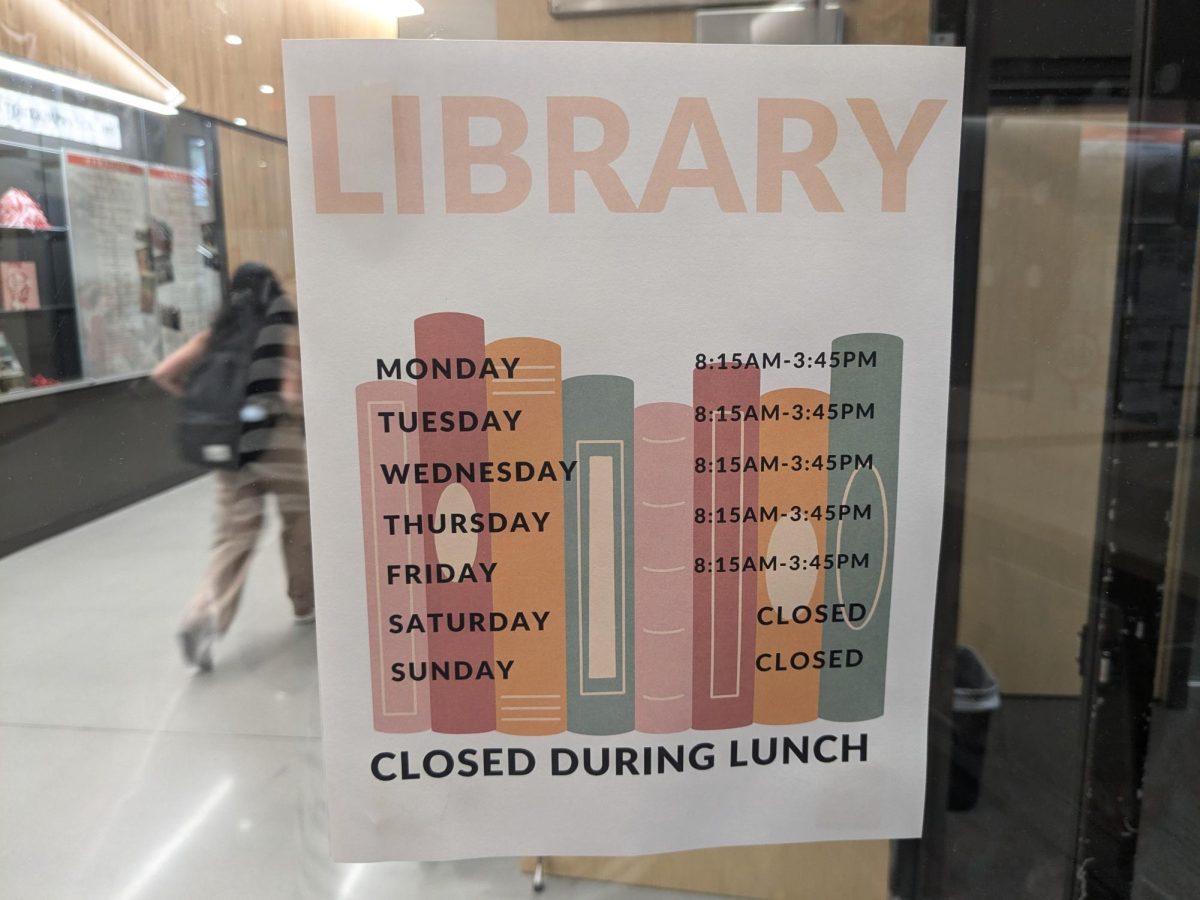

One of the services at risk of dying is the school library, which is already having to cut back on hours. This year the library is closed during lunch and after school, unlike in previous years.

Librarian Lori Lieberman worries that this change will negatively impact students’ academic performance. She recalls several students who relied on the quiet environment of the library to study for classes, and whose grades could suffer due to fewer opportunities to access necessary resources.

“It’s a disservice to our wonderful students,” Lieberman said. “We’ve taken a huge step back.”

She believes that some of the community around the library has been lost.

“I think of kids who used to come to the library every day. They would come and get five books and come back the next day, get five more books. It’s hard to foster that love of reading when the library is constantly closed.”

Lieberman knows of other school librarians in Oregon who have been experiencing similar problems, highlighting a larger trend that has been growing for years. Data from the National Center for Education Statistics shows a 19% drop in U.S. school librarian positions since 2000.

“The [librarians] are just at their wit’s end,” Lieberman said. “It seems like they have groups that are against them, and state legislators that are against them.”

Facing these challenges, Lincoln staff members like Chapman want to see action taken during the 2025 legislative session in order to reverse the decline and secure a bright future for students.

“I really hope the state steps up and fully funds K-12 education and higher education,” said the principal.