Smoke covered skies, suffocating heat waves and displaced communities. The catastrophic effects of climate change have become increasingly pressing. This summer, Portland faced consecutive days of record-breaking heat, as high as 108 degrees fahrenheit, according to The Oregonian.

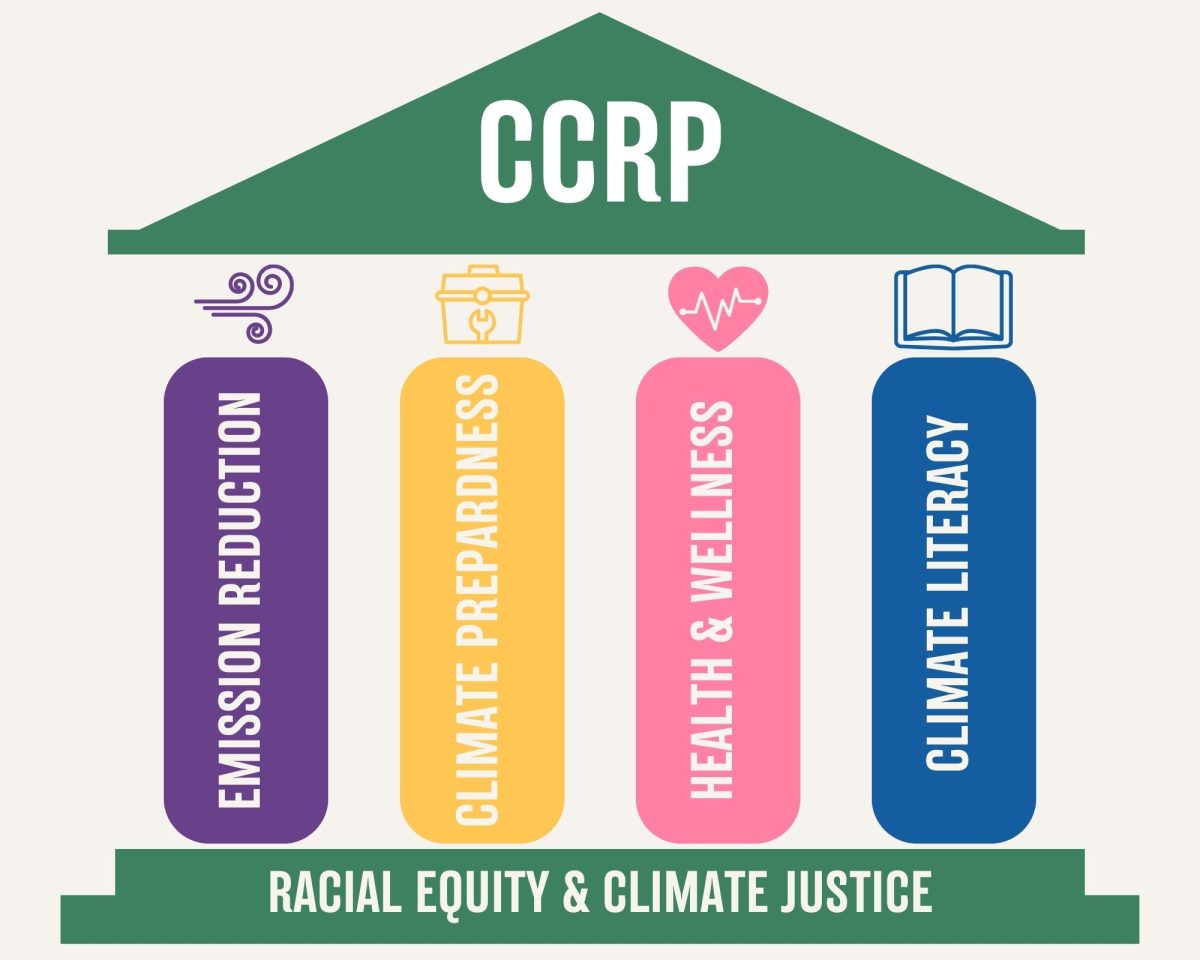

In March 2022, Portland Public Schools (PPS) passed the PPS Climate Crisis Response, Climate Justice and Sustainable Practices Policy (CCRP).

Kat Davis is the advisor for climate justice. She works for PPS to oversee the district wide implementation of the CCRP. Davis explains how the policy is the result of decades of incremental climate related initiatives led by students, parents and educators who demanded a more holistic climate policy and accountability.

Looking at the CCRP’s text, the policy’s key objectives include reaching net zero emissions by 2040, preparing schools for the effects of climate change and engaging staff and students in climate solutions, climate resiliency and climate justice practices. All while prioritizing frontline communities and vulnerable populations.

This past year, Davis says she has been playing a balancing game with PPS’s 81 schools in order to kickstart climate related programs.

“Every single aspect of this policy is in a different place of progress across the district,” said Davis.

Davis recognizes the equity component of implementation. She explains that oftentimes, schools in areas most affected by climate change have the least resources to combat it.

“My goal is to better communicate and elevate all the really cool stuff that’s already happening, and then also build out support structures and systems to better support schools that need those services,” said Davis.

At Lincoln High School, the CCRP can be seen in climate-related workshops for teachers, climate curriculum in IB Geography and FLI classes, energy saving lights/air conditioning systems, solar panels and other infrastructure improvements according to Principal Peyton Chapman.

“Currently, Lincoln is being powered by around 28 to 30% green energy,” said Chapman.

Similar efforts are underway in the ongoing modernization of Benson Polytechnic High School. Dan Malone, the Vice Principal of Modernization, is optimistic about the future of climate-friendly schools as improvements and green technology evolves with each rebuild.

“By the time we finish, [Benson] will be the most energy efficient school in the district,” said Malone.

Danny Cage, a member of the Multnomah Education’s Service Director Board, believes that PPS’s climate policy can be a test pilot for greater statewide initiatives:

“A lot of the climate action we see in education is happening at the federal level and the state level, that’s a resource-down model,” said Cage. “Here we don’t have that, there isn’t a mandate for school districts to create climate plans by the state.”

Chloe Gilmore is the co-president of Lincoln’s Environmental Justice Club and co-founder of Sunrise PPS, which aims to pass a “Green New Deal” for schools nationwide. She believes that the policy can be improved, and wishes to see a more explicit commitment to intersectional and comprehensive climate education for all grades in schools.

“How are we going to grow a new generation of climate justice leaders if they’re not taught about those issues in school?” asked Gilmore.

If students want to get involved with the implementation of PPS’s climate policy, Davis encourages students to apply for PPS’s Climate Justice Youth Advisory group, sit in on Climate Crisis Response Committee meetings, and follow the PPS Climate Justice website for more opportunities.

“It’s about coming together as a community to build a strong network of changemakers,” said Davis.

Additional reporting contributed by Ekansh Gupta.