Teachers reflect on lack of diversity in Lincoln staff

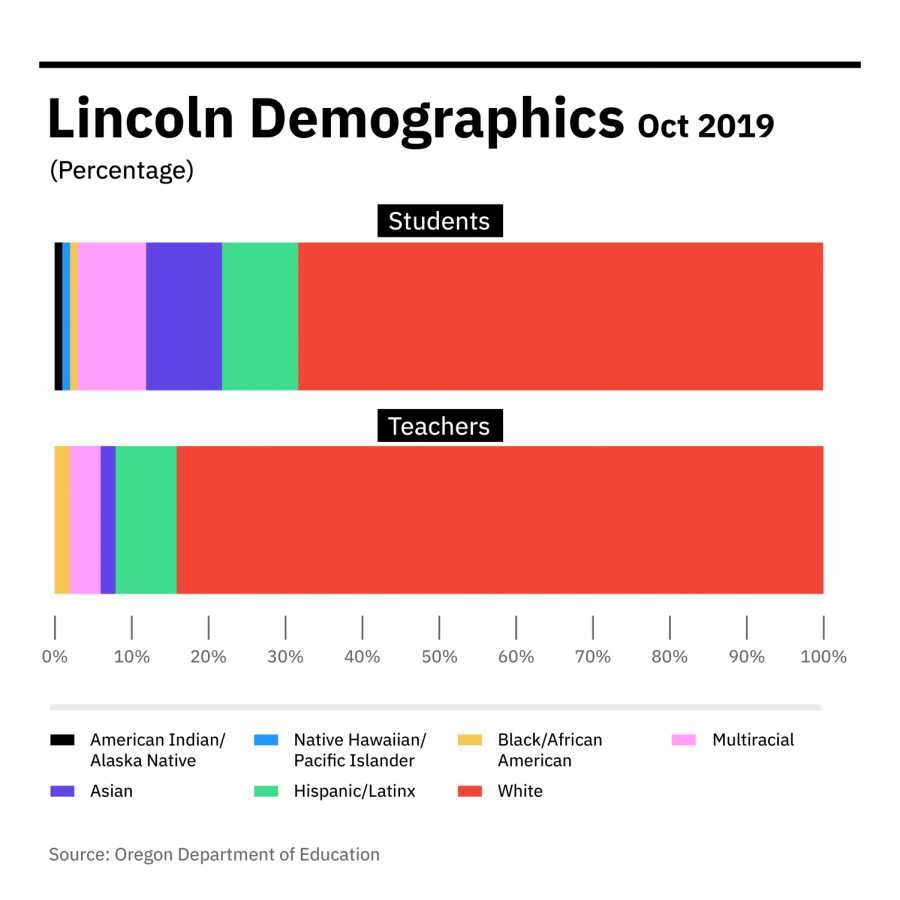

Lincoln’s 2019 demographics for staff and students broken down by race. The school, already one of the whitest in Portland, has an even smaller percentage of teachers of color.

January 16, 2021

According to the Oregon Department of Education, white teachers made up 84% of the teaching population at Lincoln during the 2019-2020 school year.

Math teacher Ricardo Alonso, who identifies as Afro-Cuban, is one of the few teachers of color at Lincoln.

“My personal experience has been good,” Alonso said. “I believe I am treated fairly by admin, staff and students, and [I] have not had any experience of overt racism directed to me. I understand that [has] not been the experience of everyone like me.”

According to a 2016 study, students of all races— white, Black, Latino and Asian— have more positive perceptions of their teachers of color than they do of their white teachers. So, why don’t U.S. schools have more diverse teaching staffs?

The U.S. Department of Education predicts that, by 2024, students of color will make up 56% of the student body in public schools. Yet, a 2017-18 survey conducted by Education Week estimated that 79.3% of public school teachers are white.

“I’ve never worked anywhere so white, I mean, co-workers and students,” said Trevor Todd, who racially identifies as white and is an IB and Dual Language Spanish teacher.

In the 2019-2020 school year, Hispanic-identifying teachers made up eight percent of the teaching population at Lincoln, followed by four percent of multiracial-identifying teachers and two percent of both Asian and Black/African American-identifying teachers. There were no American Indian/Alaska Native or Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander-identifying teachers.

“We obviously need to be more intentional about hiring racially/ethnically/culturally/nationality diverse faculty members,” said Spanish teacher Pablo DiPascuale, who identifies as Hispanic-White.

Some Lincoln teachers believe that this lack of diversity in the teaching staff throughout Portland Public Schools (PPS) is due to the fact that Portland– the whitest metropolitan city in America– is not appealing to many teachers of color.

“I feel that even though there is not much diversity in our city, the neighborhoods are very racially segregated and therefore schools demographics show such segregation because of current school boundaries,” Alonso said. “I believe that the city and state should do something about housing affordability and zoning so that our neighborhoods are more racially and economically diverse. That will have an impact in school demographics.”

Chris Buehler, a white-identifying social studies teacher, agreed.

“Portland isn’t super diverse and PPS has struggled to recruit teachers of color,” he said.

Principal Peyton Chapman also recognized that, in recent years, Lincoln has not been able to hire many positions due to declining enrollment caused by redistricting.

“Despite this challenge, we have worked with the Lincoln Foundation to help create positions that didn’t exist whenever we’ve had the opportunity to hire diverse teachers,” Chapman said.

“PPS, and [Lincoln], needs everyone’s help to increase the diversity of our applicant pools, especially during a state and national teachers shortage.”

Maureen Kenny, a white-identifying science teacher, has noticed that Lincoln has struggled to retain teachers of color.

“I know that if there are qualified candidates of color, they always get interviewed and often offered jobs,” Kenny said. “At the same time, I think we have lost teachers of color due to the lack of diversity and awareness at our school.”

Buehler believes that hiring more staff of color is crucial to the Lincoln community, but recognizes that the Lincoln staff consists of many white allies.

“If PPS and Lincoln cannot recruit teachers of color successfully, it’s essential that we have a staff at Lincoln that critically understands issues of racial injustice and is trained to support and address the needs of students of color,” Buehler said.

Amy Loy, who identifies as white, is Lincoln’s AVID coordinator and an AVID 10 teacher. She believes that PPS isn’t following through on their goals to increase diversity in their teaching staffs.

“PPS does not seem to be doing anything tangible to change the status quo,” she said. “While lip service is [paid] to valuing a diverse teaching staff, little to no actual resources are dedicated to recruiting and retaining teachers of color.”

Other teachers agree.

“I know the recruitment and hiring of more ‘racially and linguistically diverse and culturally competent’ teachers, among others, is one of PPS’s Racial Educational Equity Policy goals, but just stating it doesn’t make it happen,” said Julie O’Neill, a white-identifying Anthropology teacher.

PPS did not respond to repeated requests for comment, but does have a page on their website regarding racial equity and social justice.

Lincoln administrators say they have tried to increase the diversity of applicants in PPS and at Lincoln in the following ways:

- Screening PPS applicant pools and prioritizing racially and ethnically diverse applicants to include in interviews.

- Hiring racially and ethnically diverse support staff and working with them to become teachers by providing flexible schedules and opportunities for student teaching at Lincoln.

- Directly recruiting applicants from charter schools and personal contacts.

- Including racially diverse students and staff on community-based interview teams to help show applicants the diversity of Lincoln and include racially diverse opinions in their selections.

- Creating classes such as Education 101 in partnership with Portland Community College to help encourage students to become teachers, and offering courses such as Gender studies, Critical Race Studies and other classes where teachers’ passions and commitment to diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) are highlighted and motivating for students who may want to follow in their footsteps.

While Lincoln has been working towards their goals in increasing diversity, Chapman recognizes that it is challenging to attract applicants with Lincoln’s current demographics.

“Most educators today are becoming teachers to help be the change they want to see in the world,” Chapman said. “The values of these educators are in line with our mission and vision but until Lincoln becomes more racially and socioeconomically diverse it will be harder and harder to attract diverse applicants who prefer to apply to schools with more racial and economic diversity such as Madison and Roosevelt.”

Todd recognized Lincoln’s efforts.

“Since I’ve been here, I get the feeling that our administration has the intention to hire teachers of color, and some of my more recently hired colleagues seem to reflect that intention,” he said. “But the numbers can’t be ignored. We’re still a very white institution.”