Lincoln students voice their concerns over lack of BIPOC representation

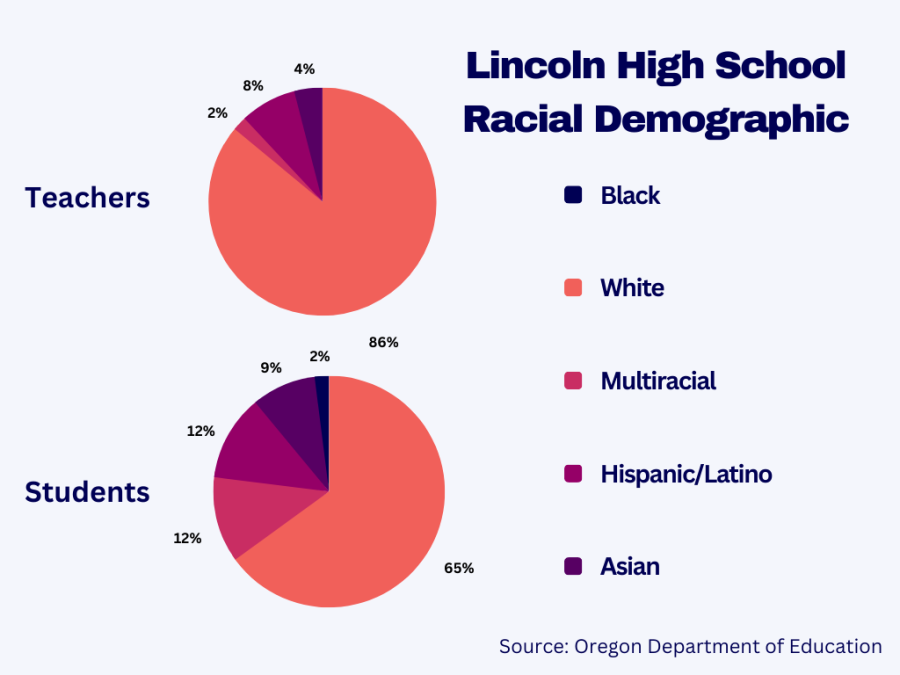

A graphic depicting Lincoln High School’s demographics.

February 16, 2023

Many students think of Lincoln as a progressive, open minded school inclusive to everyone. However, due to the lack of Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) representation in its teaching staff, many students feel that the school doesn’t live up to its reputation.

According to last year’s Profile from the Oregon Department of Education, 86% of Lincoln’s 73 teachers were white. 2% of teachers identified as multiracial, 4% as Asian, and 8% as Hispanic/Latino. 0% of teachers at Lincoln were Native American, Pacific Islander or Black teachers.

This negligible number of BIPOC educators has led BIPOC students to not fully resonate with their experiences at school.

“The lack of BIPOC teachers and staff has definitely made me feel not centered,” said Nyilah Lewis, a Black junior.

“It’s really hard to identify myself in the educational system when it’s very rare to see BIPOC professionals around. It’s weird when you walk around the hallways and don’t see people who look like you; it can be an alienating feeling sometimes,” said sophomore Ali DeShaw, who is Arab.

Students also said the school could be doing better when it comes to teaching about race-related topics.

“I feel like BIPOC students take a big chunk of that work and do it themselves. Right now we’re doing Black Lives Matter presentations, week of action [and] clubs,” Lewis said. “Ethnic studies, history classes, they’re just now including race into courses … [English classes] teach about racism in books, or they have Black authors, but I don’t think that is necessarily teaching us anything.”

While students agree that it is nice to have courses like Ethnic Studies, students can’t properly understand race with just textbooks.

“I think they do a good job on teaching the things that need to be taught, but they also don’t go any further than that, and that’s kind of hard because when you reach just the bare minimum,” DeShaw says. “If we had a more in depth curriculum, then we would have a better outcome on the understanding of history as a generation, which would be helpful [outside of] school.”

Classrooms’ abilities to have comfortable conversations about race is also lacking.

“In history classes there’s many teachers that try to include race,” said junior Jesper Lesher, who is white. “But I feel like other teachers try to neglect anything that has to do with it.”

Students think there are ways the school could increase diversity and better treat its BIPOC students.

“The area we live in is predominantly white,” said Lesher. “Therefore the students are going to be white as well. Expanding areas of the school’s reach would bring in more teachers and students of color.”

On the other hand, investing in BIPOC students who already attend Lincoln could be the way to get more BIPOC teachers in the future.

“I think you have to reach out to more people who are currently in education, because I can tell you that I know a lot of my friends who are [POC] have gotten into education in Portland,” says DeShaw. “And maybe looking at who’s coming into the teaching field instead of who’s been in it, because if we’re going to make a change it will probably come with new people as well.”