New tutoring program takes fresh approach to education

Advancement via Individual Determination. That is the goal of Lincoln’s newest tutoring program – call it AVID – introduced this year.

The program is a nationwide system for student support that runs from elementary to high school. A $1.5 million grant from Nike School Innovation Fund has allowed high and middle schools across the state to implement it.

At Lincoln, AVID takes the form of a four-year elective. Students have to apply for a spot, including justifying their interest in the program and affirming their dedication in an interview and a written application. Those that enroll are not just typical Lincoln students, however.

“There isn’t just a single profile for an AVID kid,” says Spanish teacher and Latino student union (Mecha) advisor Melinda Gale, who also teaches the class and is the AVID coordinator.

“It could be that they [would be] a first-generation college student. It could be an issue of economic hardship. It could be an issue of being an underrepresented population in a very white school. That’s not always the case for AVID programs, but at Lincoln, it’s certainly a factor.”

So what unifies the mish-mosh of AVID students?

“They’re very motivated and determined and ferociously hard-working.”

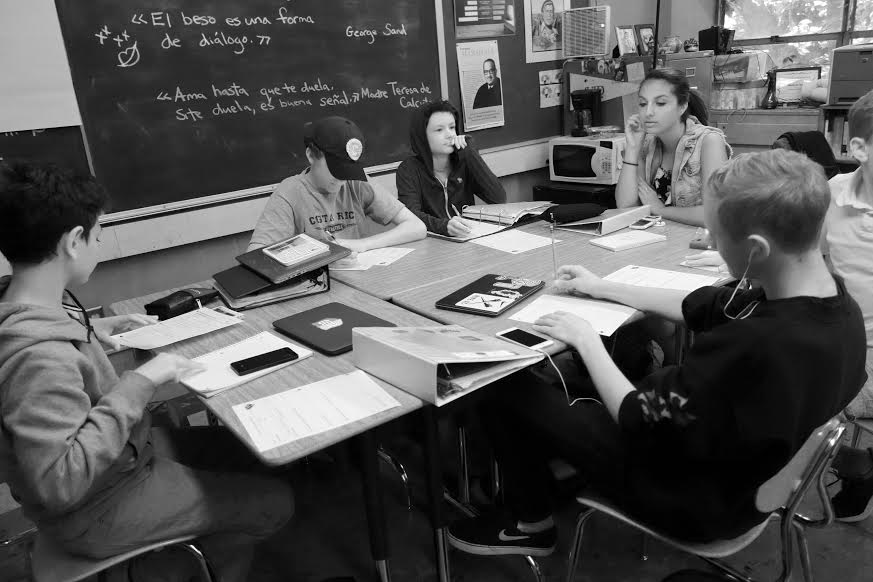

AVID takes a different approach to learning than previous tutoring programs, such as Peer Advocates. Instead of teaching students the “what” of learning, it teaches them the “how.”

The tutorial program] “aims to give students the tools they need to solve their own problems rather than giving them the answers,” says Gale.

The class is a lot more than simply Gale teaching, though. So far, five seniors and three Portland State University students have been trained as tutors to assist the class.

Danielle Zusman, Mackenzie Johnson and Azadeh Pournaderi are three of the five seniors who trained. All three have experience with tutoring and underwent an application process.

“It sounded a little more interesting and a little more organized than the regular practice of being a peer advocate,” says Johnson. “The students are very prepared. Sometimes when you tutor, at least in my experience, some kids don’t really want help. Other ones are okay. But the kids in AVID are like ‘this is what they need help with.’ ”

This seems to be a consensus among the tutors.

“The kids want to be here,” says Zusman.

Pournaderi sees that as well. “That’s why I got interested in it, just because everyone wants to be here.”

That’s certainly the case for freshman Mitchell Stoner, one of the 20 enrolled in the elective, not including pending applications.

“I feel like I’m learning a lot,” he says. “It’s kind of nice that you get a little bit of a challenge.”

He’s referring to the pre-IB nature of the course. While International Baccalaureate classes are not required for AVID students, the program aims to prepare them for rigorous upperclass and college work.

In other words, it’s no walk in the park.

That’s not to say that all AVID students are necessarily focused on university, though.

Carissa Yallup has other reasons for applying.

“Most of the people here say it’s because of college. I’m not really sure if I want to go to college,” she says. “I’m here because it’s so much easier to catch up and stay organized and it will probably help me get to college if I end up going.”

While there might be students enrolled specifically in a course for AVID, its progressive teaching strategies are not confined to that one classroom.

Over the summer, teachers were trained in Denver on the program’s best-teaching practices, which left many enthusiastic.

“It was like: We need to do this for all kids, why are we just doing it for AVID kids?” Gale says.

And that’s what ninth-grade teachers are trying to do. According to Gale, freshman teachers have implemented the strategies across the curriculum. They have infused the grade with AVID strategies, which Gale finds “pretty cool.”

In future years, she hopes for the program at Lincoln to be self-sustaining, as opposed to dependent on funds from Nike.

But for now, the program seems to be doing just fine in terms of helping kids.

“With high school, you have a challenge looming in front of you,” Stoner says, “but I feel I can take it on.”