Tribal history to be taught in schools

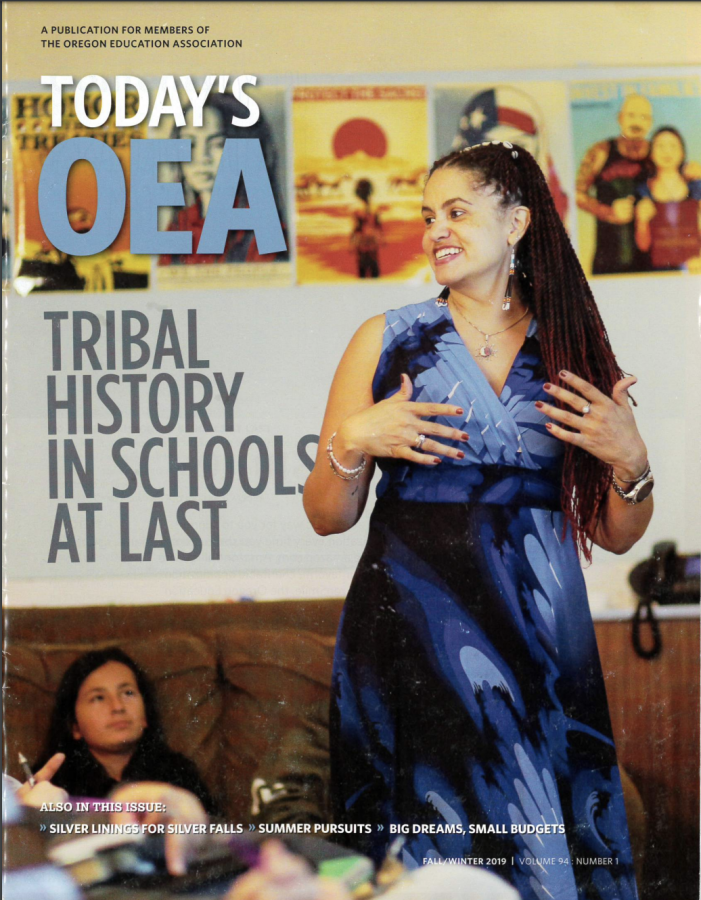

The Today’s OEA Magazine cover from Fall/Winter 2019 features information on how Oregon schools will finally teach Tribal history.

For the first time, Native history is mandated to be taught along with Oregon history.

Senate Bill 13 (SB13), known as Tribal History or Shared History, was set to be implemented in January of this year, with the intention of offering students an authentic education about the Native American experience in Oregon. The bill comes after decades of hard work and persistence from Oregon’s nine federally recognized tribes.

Native history, a large part of the state’s history, has been largely overlooked in many schools.

Senior Lenna Espinoza, who identifies as Mestiza, explains that, while it is a huge gain for Indigenous people to finally have their history learned, there are still concerns. Espinoza worries about who will be recruited to teach this history.

“I worry that perhaps wounds will be deepened,” says Espinoza.

Espinoza is also concerned with white saviorism.

If Native history isn’t taught, “The idea that white people have an inherently further developed cultural society is reinforced. Without that history we find ourselves living the lie told to us by ignorance of the Native story,” she says.

Espinoza’s fears are common among Native communities and educators.

In Katherine Watkins’ article “Tribal History Comes to Class” from Today’s OEA [the Oregon Education Association] magazine, Watkins discusses how her focus as an Indigenous educator centers around the voices of Native Americans.

“Moving away from teaching about Indigenous people to learning from Indigenous voices,” says Watkins.

Espinoza says that despite the challenges teaching Native American history presents, it is an integral part of American history.

“Without it, the history we grow up reading is a lie. … [learning] the story of the Native struggle tears down a lot of the falsities that white children grow up believing,” she says.

Anthropology, political economy and mindful studies teacher Julie O’Neill also worries about pushback from the white student body.

“If there is a pushback, it is to the idea of ‘identity politics’ generally – those people who think that if any group is singled out at all that somehow that act in itself is racist – the ‘aren’t-we-all-Americans-now’ color-blindness,” says O’Neill.

However, O’Neill also believes the law is necessary.

“SB13 will force an acknowledgment, at the very least… of the Pacific Northwest’s relationship with the Indigenous people who lived on this land before colonization and where they are now,” she says.

O’Neill believes that there is still lots of potential for learning.

“Indigenous worldviews offer a wonderful counter-narrative to individualized ‘capitalist culture.’ Tribal groups all over the region are leading the fight against fossil fuel extraction in the Northwest and Canada, and many tribes are working diligently to bring back lost languages, ethnobotany and economic independence,” says O’Neill.

Teaching white kids Native history is important, says Espinoza, but the idea is also to include history that is more representative of kids in the classroom.

“I want that powerful moment for the multitudes of Native children that live hearing their story told from white lips,” says Espinoza.