PPS Special Ed is understaffed, says Lincoln teachers

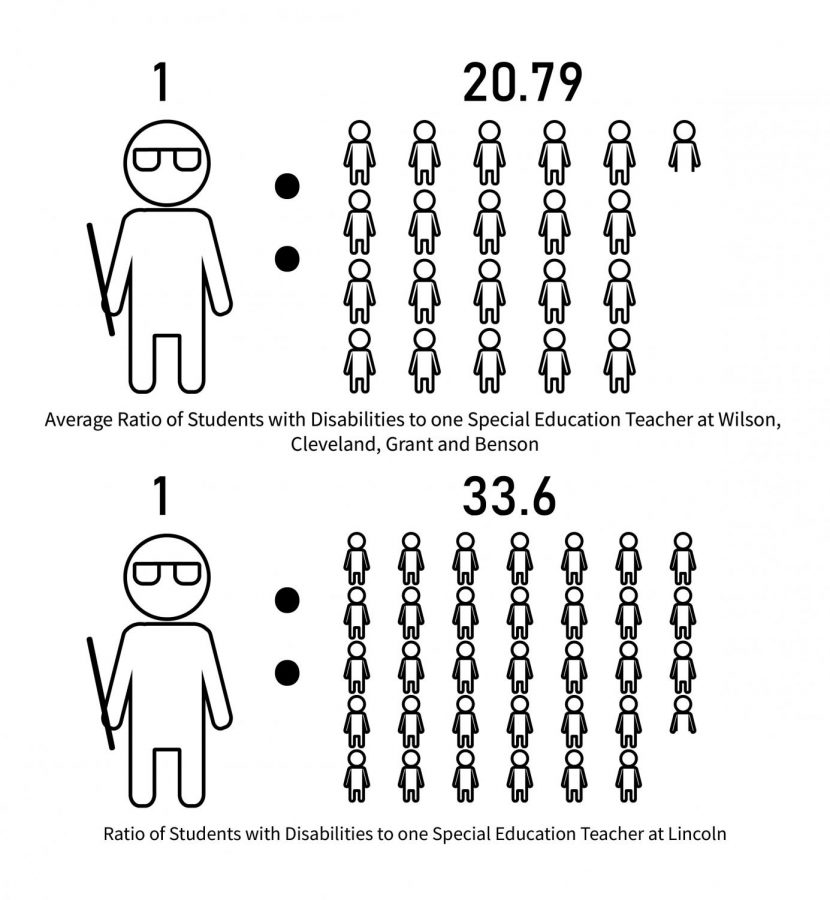

The graphic above shows the ratio of Special Education teachers to students at Lincoln compared with the other PPS schools, showing that Lincoln has almost 13 more students per teacher than other schools shown.

Correction (April 6): Special education classrooms are loud because they are adjacent to other loud classrooms. Room 168 is loud because it is next to the choir classroom. Room 151 is loud because it shares a partition wall with Health classes.

Due to a formula used by Portland Public Schools (PPS), the ratio of special education teachers to students with disabilities at Lincoln is significantly larger than at other schools in the district.

The number of special education teachers delegated to each school in PPS is decided using the percentage of total students with disabilities that attend the school. In other words, if two schools have the same percentage of students with disabilities, even if one school has a greater number of total students than the other, both schools will be delegated the same number of special education teachers.

Currently, Lincoln has three special education teachers– two full-time and one part-time– that serve 84 students with disabilities.

“The formula used to calculate no longer works when you get to the high school level,” says Scott Fitzpatrick, who has been teaching in special education for 29 years. “When I worked at Robert Gray Middle School, we had two special education teachers and Robert Gray [has a] population of around [550 students]. We have [approximately] the same amount of special education teachers here, but the population is something like 1700. So the service that I can provide the student is thinned out.”

According to individual school websites, Wilson High School has a student-to-teacher ratio of 23.6 to 1, Cleveland High School has a student-to-teacher ratio of 16.9 to 1, Grant High School has a student-to-teacher ratio of 19.3 to 1 and Benson Polytechnic High School has a student-to-teacher ratio of 24.8 to 1. Lincoln has a student-to-teacher ratio of 33.6 to 1. Because special education teachers are responsible for so many Lincoln students, it can be difficult to support their needs.

“If we had more special education teachers that could sit down and instruct, [we would have] more support for those students [and it] would make it such that they could get more work done,” says Fretta Cravens, a paraprofessional who has been working with students with disabilities at Lincoln for 16 years.

On a typical day, special education teachers at Lincoln will work with their students one-on-one, and, in any spare time that they have, complete paperwork regarding the students they are responsible for. Because of the limited number of teachers available, supporting all students’ needs can be challenging.

“We have some students that [have a] range of… abilities to learn. So, if you don’t have somebody that can work with a person at their level, then they’re not getting served at the full potential we can be serving them,” says Cravens.

To help support these special education teachers, Lincoln does have a part-time speech pathologist: Cate Lopez. But, because she is only on-campus on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Fridays, it can be difficult to fully support the students who need it.

“When you have a part-time teacher, then they’re not here all the time, and sometimes the students…need help then and there, [but no one is there to help them]. So that’s a problem,” says Cravens.

In addition to the challenges that have come with the limited number of teachers working in the special education program, students often struggle to focus because of the placement and lack of resources within their classrooms.

“Both of the classrooms we have are very noisy, [and] we don’t have the right place to have our students work all the time,” says Cravens. “We’re not supplied computers or Chromebooks [except] a couple of old computers the school district doesn’t [want to] bother with, so we have to figure out how to do that all within our own system.”

Although this lack of support can make it hard for some students to stay on task and get the help that they need, many teachers throughout the school are acting as a support system to serve students with disabilities.

“I’m amazed at the work effort and attention that teachers are giving our kids with disabilities. I think that they’re, in many ways, carrying some of the burden of our low staffing of special education. They’re [doing] phenomenal,” says Fitzpatrick.

Cravens believes that the larger student body should aim to be more inclusive in order to keep students with disabilities from feeling isolated. She says doing so can help students with disabilities feel better about themselves while simultaneously encouraging them to complete their work.

“Students with disabilities sometimes get very isolated… but student peer-to-peer communication is really important,” says Cravens.

Next year, the number of teachers allocated for the special education program is set to remain at two full-time teachers and one part-time teacher. The classroom space allocated for these students will also remain the same.

“We’ve been trying to highlight this as an issue for a long time. And I think the building and administrators understand it, and we appreciate that,” says Fitzpatrick. “I just get disappointed because the things that I want to do, I can’t do for [the] kids.”