Lack of diversity: a long lasting issue at PPS and Lincoln

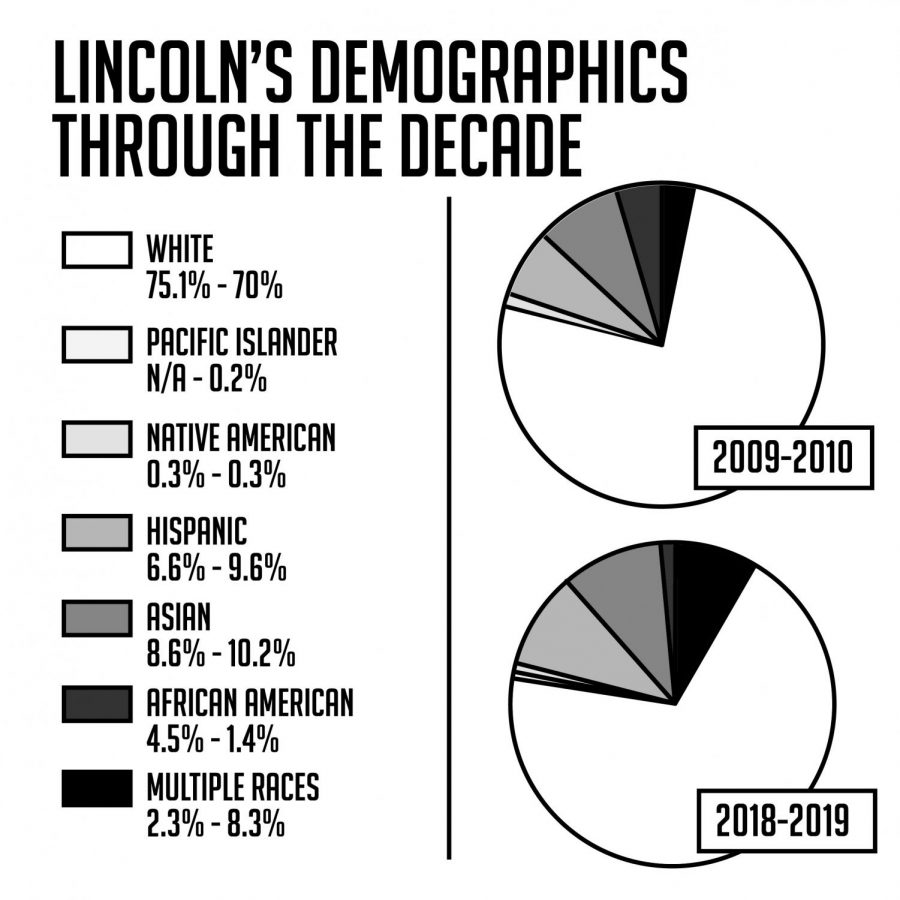

Data collected from the PPS Enrollment Profile over the past ten years.

Correction: The original version of this article incorrectly stated Deja Preusser’s racial identity in an attribution. Preusser identifies as mixed-race.

When describing Lincoln, both attendees and outsiders refer to a common stereotype: white. After looking at enrollment from the past decade, this stereotype has proven true.

At Lincoln, enrollment of each racial and ethnic background has ebbed and flowed, according to PPS records. From the 2008-2009 school year to the 2018-2019 school year, the number of white students decreased from 75.1 percent to 70 percent, African American enrollment decreased from 4.5 percent to 1.4 percent, the number of Asian students increased from 8.6 percent to 10.2 percent, Hispanic enrollment increased from 6.6 percent to 9.6 percent and Native American enrollment held at around 0.3 percent.

Lincoln was predominantly white even 10 years ago. Although the number has decreased, almost every student interviewed considers the school to be “too white”– even white students.

“I don’t think Lincoln fits [my] idea of diversity at all. All of my classes at Lincoln are overwhelmingly white and lack very little racial or socioeconomic diversity,” says junior Jason Abrams, a member of the Lincoln Diversity Committee who identifies as white.

Abrams believes that this lack of diversity has a negative effect on the students at Lincoln.

“I believe that people from different backgrounds all bring something new to the table to discuss and entertain, making it very important to hear from diverse groups,” says Abrams. “I think that Lincoln’s lack of diversity creates a lack of open-mindedness and free-thinking for our students and it should be fixed.”

As the enrollment of white students at Lincoln decreased, the number of African American students did as well. Both the decrease, as well as the fact that the numbers have always been so low, are not a surprise to Deja Preusser, the leader of Sisters of Color.

“Portland’s history clearly shows a trend of gentrification and the exiling of black and brown communities, so I think it’s deeper than just Lincoln,” said Preusser.

Preusser remembers a previous school she attended, that, in comparison to Lincoln, was more diverse. In that school, she believes students were able to be more empathetic and educated on perspectives different from their own.

Preusser, along with other students affected by Lincoln’s lack of diversity, are working to find a solution in the Diversity Committee.

“We’re trying to enact change. We’re all very dedicated to shifting the tone that we have here at Lincoln,” said Preusser.

Similar to African American students, the enrollment of Pacific Islander students has remained small, holding under one percent of total students.

“[I feel] underrepresented and isolated,” said senior Raya Rojales, who identifies as Pacific Islander.

Similar to Preusser, Rojales has experience in schools that have a higher population of people of color. In these schools, located in places like San Francisco, Calif. and Oahu, Hawaii, Rojales felt like she fit in.

“In communities with a lot of people like me, it was easier to make friends, connections, and talk with people because we can relate,” said Rojales.

Unlike African American and Pacific Islander enrollment, the number of Asian students at Lincoln has increased.

Senior Anya Anand, who identifies as Asian-Indian, recognizes the lack of diversity at Lincoln but believes a change is not something that can be forced.

“I think that Lincoln definitely tries to fit [a certain] idea of diversity and they make a lot of efforts to move towards a more diverse community, but the fact is that we are located in downtown Portland, and we have a predominantly white population in our school,” says Anand.

Although the lack of diversity is a difficult problem to solve, Anand believes there are potential solutions.

“Overall, I think that there isn’t a lot of diversity and representation at Lincoln, or as much as I’d like there to be… I think one of the biggest things we can do is to incorporate more diversity into the lessons in the classroom,” says Anand. “A lot of students, including me, feel alienated while learning materials in the classroom because they don’t find they relate personally to what they are learning. I think that this could be a first step in the right direction of supporting diversity at Lincoln.”

The enrollment of Hispanic students has also increased. Despite this increase, many Hispanic and Latin American students still do not feel represented.

“Sometimes, we feel out of place…being the only brown kid in a classroom or school event. Also, most of us, being mixed ethnicities, feel awkward in class discussions because we feel as if all people of color get grouped together when talking about race, and people turn to us to speak for all brown people,” says Sam Coltman, a member of the student-run group MEChA.

Coltman, and the rest of MEChA, believe that Lincoln needs to shift its stance on diversity.

“Just look[ing] at the PPS school district, we can see that the schools that are predominately white are wealthier schools,” Coltman says. “Diversity is not taken note of at Lincoln, and it should be changed so people like us, MEChA [leaders], can feel more included and get the same education and respect as our white peers.”

Unlike other demographics, enrollment of Native American students has remained similar over the past decade: less than 1 percent.

“The sad truth [about the low percentage of Native Americans at Lincoln] is that it’s because there are not many of us left,” says senior Cody Dean, who identifies as Native American.

Dean is unhappy with the way Lincoln tries to make him feel like he “fits in” and how others try to empathize with him on problems they “know nothing about.” His potential solution to the problem involves the whole student body.

“I think it’s more or less what we as students can do,” says Dean. “I think if we all took a step back and looked at this massive bubble that we’re in, we would finally recognize the differences between honoring a culture and race or tokenizing and appropriating it.”

Note: The Cardinal Times recognizes that PPS demographics do not reflect all identified ethnicities of Lincoln students, and groups certain students into larger groups.