Why students don’t report

March 24, 2018

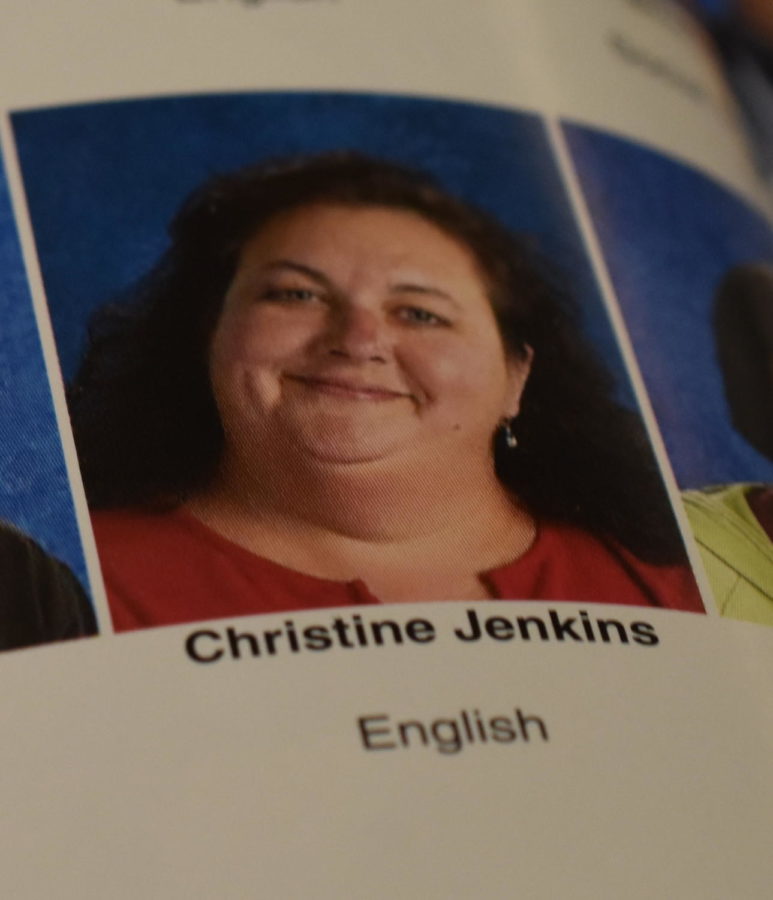

Christine Jenkins pictured in the 2008-09 yearbook. Jenkins was accused of pursuing a relationship with a freshman that year.

The first obstacle victims face in reporting misbehavior is deciding who to go to. The Cardinal Times found that when asked about this, many current students did not have an immediate answer and had to think it through.

A common initial response was parents, who could then help report to school administrators. But as junior Jessica Motley acknowledged, “not everyone is in the situation at home where they can tell this type of thing to their parents.”

Another possibility mentioned by students was to go to counselors and administrators.

“It takes initiative to come up with [an answer] that should be intuitive,” said junior Josh Gregory, referring to the decision about who to report to. He said this was especially worrying given that victims in this situation may have strong emotions clouding judgement.

But even when a victim does know who to report to, a litany of other factors can hold him or her back.

The power dynamic between students and teachers is a major reason students are disinclined to report abuse, said English teacher Amanda Jane-Elliott. The student may feel less empowered to speak up because the teacher is in a position of authority, she said. A student might be worried about how her or his grades could be impacted.

The fear of repercussions is also a deterrent. In today’s digital world, it is much easier for news, such as the report of misconduct by a teacher, to spread among students, said Elliott. “The minute something happens, it’s on social media, and everyone knows,” she said.

This fear may stop some victims from reporting. “I can’t imagine anything more difficult than coming to school when everyone is talking about what happened to you,” said another teacher who agreed to speak on condition of anonymity.

This fear is backed up by medical studies. Sarah Dobey is a licensed professional counselor and clinical director at the Integrative Trauma Treatment Center in Northwest Portland. She has worked with victims of sexual abuse and knows the many difficulties victims face in coming forward.

“There’s a lot of neuroscience that shows that in [reporting] situations, our amygdala (which controls fear) is activated and parts of the brain that control speech shut off,” Dobey said.

Another factor that influences whether students report is that sometimes they don’t recognize that the teacher’s behavior crosses the line into sexual misconduct.

“As a 15-year-old kid, I thought I was mature and aware enough to recognize [Jenkins’ behavior] for what it was, but it took a long time,” Zerpa said.

Though not speaking on Jenkins’ case, Elliott says that this difficulty in recognizing the behavior can be a major issue. “Even if the student thinks it’s a ‘real relationship,’ it’s not, because the power dynamic is wrong. This [justification of the behavior] not only makes it harder to report it, but even to see it’s a problem.”

Elliott said this might be exacerbated if a teacher is particularly popular or charismatic or lax about rules, such as allowing cell-phone use in class. This attitude already begins to erode some of the boundaries between students and teachers.

Principal Chapman said she saw this first hand when working in a battered women’s shelter in Washington, D.C.

“I really learned to never underestimate the power of an abusive person because it crosses all gender, racial, socioeconomic classes. A 16-year-old might not even know it’s happening. That’s the power of grooming, especially when you’re in a trusted relationship with a coach, a teacher, a priest.”

Zerpa feels that grooming may have happened in his case, and others. He said Jenkins was very well-liked by a significant portion of students and fellow teachers.

Students would often be in her room during break times and after school talking with her about non-school-related personal problems, according to Zerpa and other Lincoln alumni who were in Jenkins’ classes.

This non-academic relationship can erode the natural boundary between a teacher in his or her professional role, said Zerpa.

“If you have a ‘cooler,’ ‘hipper’ teacher that doesn’t stick to the status quo, it breaks down that barrier between teachers and students a little bit, and you start seeing them more in a ‘cool adult’ role,” he said. “So when they start doing things wrong, you start to justify that behavior.”

The 2012 case involving Sato, the social studies teacher, follows the same pattern.

One former student of Sato’s, Alex Meyer, told the Cardinal Times that the teacher fostered close relationships to students.

“He was particularly friendly with female students. He took a liking to them just as they took a liking to his charm,” said Meyer, who had Sato in 2011-12. “He was much closer with some female students than other teachers were.”

Another case of misconduct involving a charismatic educator at Lincoln occurred in May 2014, when substitute teacher Daniel Dickason filled in for a history class.

Dickason, who was 64 at the time, quickly broke down the professional barriers meant to separate teachers and students, a TSPC investigation obtained through a public records request found. He showed students his Facebook feed, which included photos of his high school prom date, a marijuana leaf and a “provocative pose with a tango dancer,” according to the TSPC.

He also allowed students to be on their phones and go to Starbucks during the class, the report said.

After developing this relaxed attitude with students, he passed one female student a note asking her to attend his birthday party that weekend, investigators found. The student felt extremely uncomfortable and reported Dickason to the administration.

He resigned as a substitute in 2014 as part of a settlement agreement with the district.

Dickason could not be reached for comment.

In his interview with the TSPC, Dickason admitted he “violated student-teacher boundaries and used poor judgment” during a time when he was “suffering from clinical depression and had an increasing problem with alcohol,” investigators wrote. He denied any romantic or sexual interest in the student.

Another consequence of raising concerns about a popular teacher: reporting can create repercussions for the student, said Elliott.

“You wouldn’t want to be the person who goes against the crowd. When you go against the crowd, you’ve upset the teacher’s life, people aren’t going to believe you and you’ll be called names – it’s a lose-lose situation.”

This was a factor in Zerpa’s case, he said.

“I basically disappeared all summer because I could not stand the messages I was getting,” he said. “Given how popular of a teacher Jenkins was, she had almost a cult following. Because she had awesome relationships with so many students who loved her, she turned to those people to make it look like I was coming out of left field with all of this.”

But the retribution against Zerpa went even further: He said he felt repercussions from other teachers for his remaining three years at the school.

“The teachers were split between ‘Team Jenkins’ and not, and I could feel which teachers still had a grudge against me. They knew, ‘this is the kid who got our friend fired.’”

Another source who requested to remain anonymous confirmed that Zerpa was treated poorly by other teachers who supported Jenkins.