Bond to rebuild LHS passes: what’s next?

A little girl among the group of volunteers and staff gathered at campaign headquarters on election night summed up with one word the feelings in the room and for students, teachers and administrators across the district: “Yay!” she yelled.

Portland Public Schools’ $790 million school modernization bond, the most expensive in the history of the state of Oregon, passed with 66 percent of the vote. The funds will rebuild Lincoln High and Kellogg Middle School, renovate Benson and Madison high schools and make $150 million in health and safety improvements across the district.

But now the real work begins. Despite the win, construction will not begin for quite a while, and no current Lincoln students will go to school in the new building.

A two-year planning period is just beginning, which includes permitting and finding a contractor, said Eleni Kehagiaras, who chaired Lincoln’s Long Term Development Committee and Master Planning Committee (MPC). Although the MPC has been working for more than a year on a design plan, and already conducted detailed evaluations such as soil samples, a newly formed Design Advisory Group (DAG) has to review those plans and work closely with the contractor on final details.

Part of the reason for this seemingly convoluted web of committees and groups is to ensure community members are heavily involved in the process. Kehagiaras called community involvement “essential.”

Further, she said, while the MPC made broad decisions such as where to place a building on the property, the DAG will address specific choices to the school, such as how much space to allocate to a certain department or where to put a facility in the building. Students and teachers will be able to work closely with the DAG on these decisions.

Chief of School Modernization Jerry Vincent said at a Feb. 8 Town Hall meeting at Lincoln that the planning period would conclude in Spring 2019, roughly around when Grant High School’s remodel, which gets under way this summer, finishes.

Plans call for the new school to be built where Lincoln’s athletic field currently sits, meaning students attending Lincoln at the time would not have to move out during construction. That means work could start right away when planning is completed, while Benson and Madison must wait until summer. With the project estimated to take three years, the new Lincoln would likely open in 2022. That timeline is subject to Board approval.

PPS Capital Project Director Erik Gerding confirmed to The Cardinal Times that a two-year planning period is starting now, but declined to comment further, citing Board discussions.

Vincent also declined to comment on the timeline until the Board votes.

Meanwhile, Lincoln will likely receive very little of the $150 million in health and safety funding, as it is to be rebuilt, even though students will remain in the building for at least five more years. This was a point of contention at the Feb. 8 Town Hall. Interim PPS Chief Operating Officer Courtney Wilton told a community member, “Our attention is on the other buildings, but we’ll respond to any major safety issues [at Lincoln].”

Kehagiaras said it is likely that water jugs will remain at Lincoln until the new building opens.

As the new building will be on Lincoln’s only athletic field and track, teams will have to find new places for practice and games. Athletic Director Jessica Russell said she will be working this summer on a more detailed plan for this, but options currently on the table include Washington Park, Jackson Middle School, Duniway Park, Providence Park, fields at Lincoln’s feeder schools and Tualatin Hills Parks and Recreation facilities.

•••

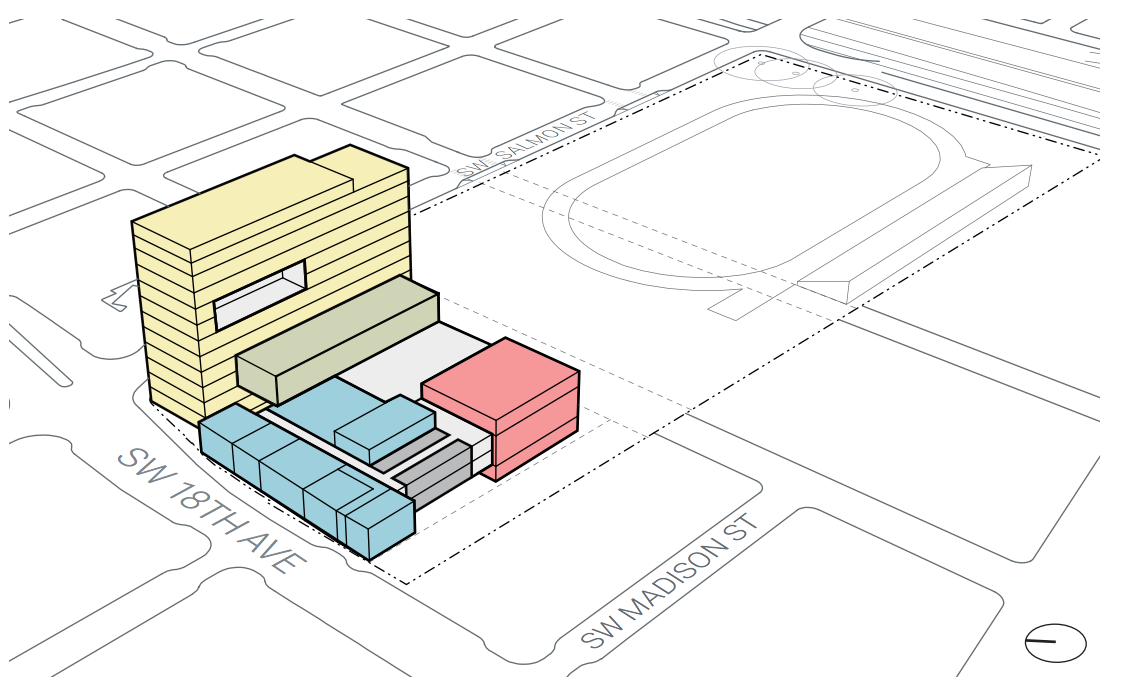

The MPC’s final design proposal calls for a radically different campus, designed to optimize the Lincoln’s small footprint.

With the building on Southwest 18th Avenue, Cardinals would have easy access to MAX and bus lines. A teacher parking lot is proposed for behind the building, at the current intersection of Southwest Salmon and 16th Avenue, along with an auxiliary athletic field, which could eventually be covered by another building.

The current design calls for a 10-story academic building, along with two gyms and a performing arts facility not stacked.

Kehagiaras travelled with several architects and PPS staff to Chicago in May of last year to explore schools with a more vertical design, which are not found in Portland.

“The overall user experience for students is better” in these vertical buildings, Kehagiaras and the team found. They said students could have shorter walks during passing time, the curriculum could be clustered in areas of the building and accessibility for students with disabilities were improved.

“[Students] could be going only 30 feet between classes instead of two blocks, like the current arrangement,” she said.

The media center will likely be placed on a middle floor, with administration towards the bottom. The current division of the grade-level lockers into halls could be divided by floor, instead, Kehagiaras said.

These plans are still to be reviewed extensively by the DAG, city planners, PPS and contractors.

•••

But for those involved with the campaign, the election was their final hurdle.

The group of around 100 at the campaign headquarters, in an office building on Northeast Couch Street, cheered and hugged when the results appeared projected on a wall.

Campaign field director Ben Katz told The Cardinal Times that he felt a “mix of relief and pure joy” upon hearing of the victory. He called the campaign “tough.”

Advocates had to overcome negative attention the district has received over the past year, including lead found in schools last summer, the resignation of a superintendent and nearly a dozen executives at the central office, and, most recently, a botched hiring effort for a new superintendent.

Leaders of the effort said they were celebrating the win not for themselves, but for current students and “generations” of future ones, as campaign manager Jeremy Wright said in a speech.

For Wright, his stake in getting the measure passed was personal, as he has two young children who will enter PPS soon, he said in March interview with the Times.

At the party, he thanked the work of his staff and volunteers, who worked to place thousands of phone calls, knock on thousands of doors and write over 5,000 postcards in a tight timeline. There were only 77 days between when the measure was placed on the ballot to when it was passed.

Many of those volunteers were students. Leading the way was Lincoln sophomore Raja Moreno, who formed a political action committee, or PAC, to advocate for the measure.

“It is our duty as both responsible citizens and as students who are suffering years of a crumbling building to stand up and make a change on behalf of the next generation of Lincoln students,” he told the Times in February.

On election night, Moreno said he felt “elation” when the results were announced, after being very anxious in the days leading up to it. He said it was a “validation of the work” he and his volunteers had put in, and thanked his fellow students for supporting the effort.

“They really made a difference,” he said.

Katz felt the same way. “Students made their voices heard on this.” One Wilson student was even a staff member at the campaign office.

Katz said it was a reminder that “students shouldn’t hesitate to make voices heard on future issues.”

In terms of Moreno’s PAC, he says he will shut it down for now, as it was formed for the specific purpose of passing this measure. However, he did not rule out re-opening it for a future issue affecting students.

But his first plans? “Sleep,” he said with a laugh.

•••

One of the biggest messages put forward by that winning campaign team was that new facilities would boost graduation rates. Now that the buildings are truly taking shape, the design and construction teams will have to keep in mind how they will actually make this rise in graduation rates happen.

Kehagiaras pointed out several ways this will happen at Lincoln, as well as Benson and Madison. The current classroom environment makes it difficult to learn, she said– temperature and ventilation issues, bad acoustics and lack of natural light are all distractions.

Last year, teachers were polled on what would they believed would improve the learning environment, and a large number noted air quality and light as top factors. Both of these would improve with the new building, Kehagiaras said.

“We’re limiting students by the environment we put them in,” she said. “Just changing that can improve the outcomes– grades and graduation rates.”

Further, the new building will have better facilities. “Our teachers bring in great knowledge and the IB program brings a great curriculum,” she said, but only so much improvement to the “academic space” can be made without improving the “physical space.”

For example, Benson focuses heavily on career and technical education (CTE), and that can be difficult with antiquated facilities. “How can you be trained to be an auto shop mechanic if the equipment you are using is 50 years old?” she asked.

At Lincoln, Culinary Arts was added two years ago, but it lacks a dedicated classroom, sharing space with the cafeteria staff.

Because they are not being prepared for the real world, some students might have no reason to remain in school. “CTE programs engage students who wouldn’t want to go to school otherwise,” she said. More space in the new buildings will allow space for more CTE classes. “The classes provide an outlet from book, book, book. They can be fun.”

The hope for all of those involved is that the new facilities can provide the next generation of PPS students, like the young girl who celebrated on election night, with a solid foundation for their future.