Reducing stigma around reporting

March 24, 2018

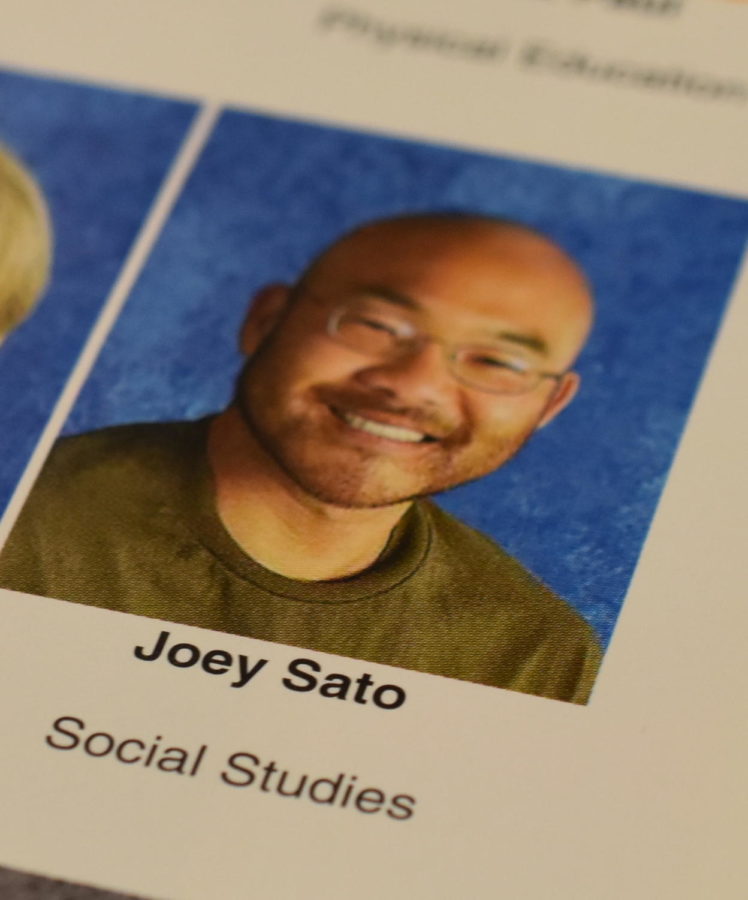

Joey Sato pictured in the 2011-12 yearbook. Sato was the subject of several sexual misconduct complaints that year.

What can be done by the school to clarify steps to take and reduce the stigma around reporting? The Cardinal Times fielded suggestions from people across the Lincoln community.

First, many said, the school needs to make clear the people to whom victims can report.

Jeff Edmundson, a former Lincoln teacher and current Constitution Team coach, proposed that this education on resources occur in conversations with counselors or at an assembly. “If you want to set the bar, it has to be verbal and direct, not some handbook that no one reads.”

However, in doing this, Edmundson warned, the school needs to make sure it is not put off as another “pro forma” message from the administration. “When you keep reminding people, they tune out,” he said.

He said he is not sure how to make the message stick.

It could be done through “a page in the planner where it is laid out, or posters,” suggested Elliott, the English teacher.

A common theme throughout the suggestions was to educate students on what behaviors cross the line – reducing the problem of students justifying teachers’ behavior.

“We need to be more explicit about the types of situations in which [students] should [report], and name it,” said Raczek, the biology teacher. She suggested perhaps folding this lesson into existing anti-bullying presentations.

Another teacher, who requested to remain anonymous, said that the school should let students know what the boundaries are and what behaviors cross the line.

The teacher suggested that this be weaved into the curriculum in health classes, which are required. “Kids are just discovering themselves as sexual creatures, so these are questions that are always on the mind – ‘am I reading too much into this, or not enough?’” the teacher said.

To reduce the stigma around “snitching,” Elliott suggests students need to work together to create a more supportive environment for those who report.

“Student activists could create a culture where students feel empowered to call things out. Students need to let each other know that they won’t be horrible to someone who says something,” Elliott said.

There is also the fear of not being believed by administrators, but Chapman, the principal, said that awareness of the investigation procedures can alleviate this fear.

Due to employer-employee confidentiality laws, Chapman said she is unable to inform the student about the result of an investigation initiated by a complaint. This may have fostered a belief among students who have reported that the administration does nothing.

“[A person who makes a complaint] may feel like ‘I have told [Ms. Chapman] this’ and nothing happened. [But] something happens when somebody comes and shares that information, but it may not be that the person was fired.

“It may be that there was a letter of expectations (which suggests ways to avoid misbehaviors by the teacher), it may be that there was a conversation, it may be that there was documentation,” she said.

Zerpa said he was contacted throughout the summer following his complaint as PPS conducted its investigation, but he was not informed of the eventual outcome of his case.

Though Chapman could not speak specifically on Zerpa’s case, the confidentiality laws likely are why Zerpa was never informed of the official outcome of his complaint.

Another obstacle is the fear of repercussions from the accused teacher. Raczek, Lincoln’s union representative, hopes that a revision in the new teachers’ contact adopted in February could alleviate one concern.

Article 25, which addresses complaints against teachers, formerly read, “If a complaint is made to a supervisor about the professional educator […] the supervisor will request that the complainant discuss the matter directly with the professional educator.”

This would have forced student victims to directly confront their abuser.

The new contract adds to the end of that sentence, “except if the complaint involves allegations of sexual conduct.”

Raczek said this is something the union strongly pushed for. “We don’t want the student having to go to talk to the teacher about this,” she said

Dobey, the trauma counselor, said that to encourage reporting, there first needs to be a focus on mental health in the education system.

“Coping skills, stress tolerance, emotional regulation all need to be integrated into the curriculum, and we need to have more professionals working in schools,” beyond counselors who have massive caseloads and a focus on college admissions, she said. Doing this will help a student cope with the trauma of sexual abuse and encourage them to come forward.

“Any sort of abuse can be very alienating,” she said.

A former Lincoln counselor, Joyce Liljeholm, said counselors’ workloads make them more impersonal to students. “As a counselor, I was concerned about students being able to speak privately with me, as our case loads were over 400 students,” she said in an email.

Chapman said that two new staff members hired with Measure 98 funds could alleviate this problem.

One of them is Judy Herzberg, a mental support counselor who will be in the counseling center 10 hours per week.

“My role is to work with students and families on emotional and mental health concerns,” Herzberg said. She receives referrals from counselors and can work with students for free and without parent consent or knowledge.

She said that as a PPS employee, she does have a mandatory duty to report abuse against a student, but all other discussions are confidential.

In the case of sexual misconduct by a teacher, she said she would talk with the student and “help them understand that it is not their fault.”

Further, newly hired student engagement coach Michelle Hardaway will help monitor attendance, which can start to decline when the student is targeted by a teacher, Chapman said.

Herzberg and Hardaway supplement the work of Gina Batliner, a licensed professional counselor who works for Western Psychological and Counseling Services, but has an office in the counseling center at Lincoln.

Batliner does bill students who come to her, so she more often works with students who have talked to parents beforehand.

Dobey, the counselor at Integrative Trauma Treatment Center, also said that the professionals and administrators who are asking students to report to them need be proactive and make themselves known on a personal level – not just a name on a poster or in an announcement.

“[Victims] need to know the person on the other end (of a report) will be kind and compassionate. Having more practitioners come into classrooms and talk about who to go to will give a face [to these resources].”

Zerpa agreed. He said he was glad that he already had a relationship with administrators. “It made it easier for me because I didn’t feel like I was telling a complete stranger what happened.”