Abused and Afraid

Is Lincoln doing enough to protect students from teacher misconduct?

April 2, 2018

A whisper in the ear. A hug lasting too long. Even a kiss on the head.

These are just some of the actions by teachers that Lincoln students in the past decade have had to consider whether to report to administrators.

But the decision hasn’t been easy. An investigation by the Cardinal Times has revealed that some students have had to weigh the desire to report against the possibility of shame and retaliation when peers or other teachers find out who “snitched.”

The Times also learned that Lincoln students are often confused or uninformed about the best way to report; and that those who do report may not learn whether their concern is being investigated or ignored.

Concerns were raised about the district’s policies on handling teacher sexual misconduct when The Oregonian revealed late last summer that Mitch Whitehurst, a teacher and coach at several Portland high schools – including Lincoln from 1986-97 – had been the subject of complaints from female students going back to the 1980s. However, no action was taken until 2015, when a male colleague reported Whitehurst for harassment.

The high-profile Whitehurst case led to a major internal investigation at PPS and calls for policy changes in how sexual misconduct complaints are investigated on the district level.

Three Lincoln teachers, including a substitute, have been reported, investigated and left the school in the past 10 years after allegations of sexual misconduct involving students, according to a database kept by the Oregon Teaching Standards and Practices Commission (TSPC).

The Times decided to trace one of these cases back to the beginning – the investigation of complaint, how the misconduct might have been prevented, and hiring the teacher in the first place – to explore how the school has improved since then and what more it could do to protect students at each step of this process.

An Oregonian editorial on Aug. 20, 2017 featured a photo of Lincoln and questioned whether PPS is doing enough to protect its students from teachers who commit sexual misconduct.

Investigating complaints

On the second-to-last day of the 2008-09 school year, the mother of Ethan Zerpa, a freshman at the time, marched into Principal Peyton Chapman’s office with a folder full of staggering evidence.

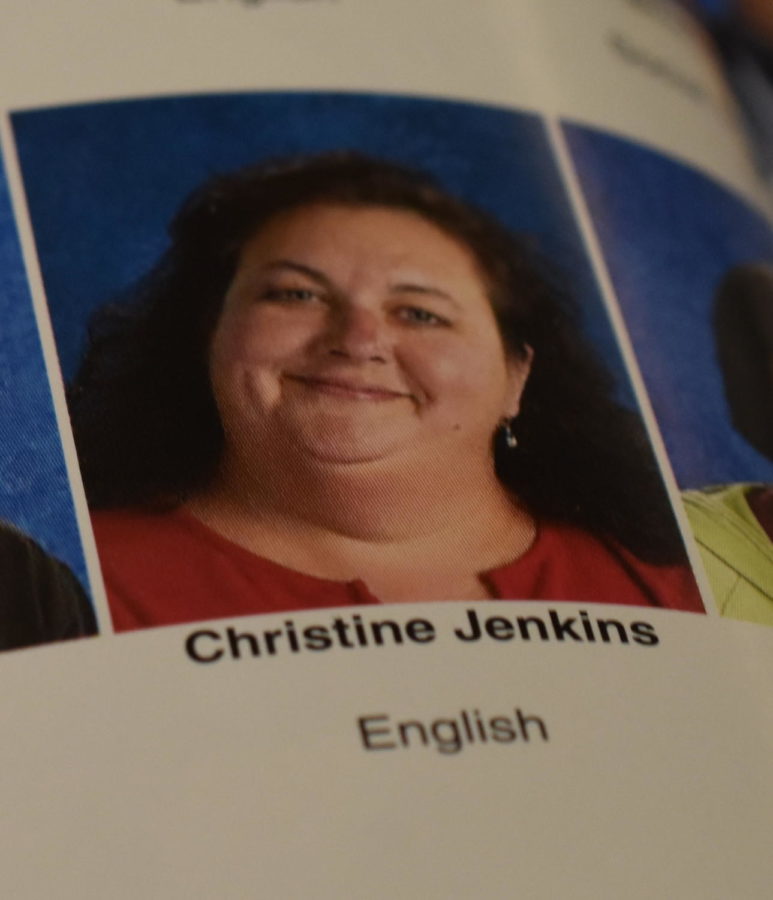

It was the culmination of months of inappropriate behavior Zerpa faced at the hands of Christine Jenkins, an English teacher, according to a TSPC investigation obtained through a public records request.

Zerpa was not a student of Jenkins, but worked with her as president of the freshman class cabinet. They planned events and, as the year progressed, Jenkins, then 44, began to foster a closer relationship with Zerpa.

“It became less about the group spending time with her, and more about me spending time with her,” Zerpa, now 24, told the Cardinal Times.

In person (occasionally alone with Zerpa) and on Facebook instant messaging, Jenkins told the freshman private facts about herself, such as her relationship with a Lincoln staff member and times she drank and smoked, according to the TSPC.

“The lines became blurred,” Zerpa said. “It wasn’t something I realized while it was going on, not until a few weeks before the end of the school year when things became more aggressive on her part.”

The “relationship” became more physical, with frequent hugs and a kiss on the cheek, according to the commission’s investigative findings.

“Even then I was finding reasons to justify why it was okay,” he said. “‘It was just Ms. Jenkins, everyone loves her,’ I was thinking.”

Jenkins took Zerpa and another student into the maintenance tunnels below Lincoln, and she wrote an obscenity about Principal Chapman on the walls, according to the TSPC. Jenkins filmed the trip into the tunnels, the investigation found, and, along with the online messages, this was a part of the evidence that Zerpa and his mother brought to Chapman’s attention.

Zerpa said he became increasingly uncomfortable with the teacher’s behavior, and he alerted his parents, who came forward.

Though not at liberty to discuss individual cases, Chapman described to the Cardinal Times what happens behind the scenes when the school receives any type of complaint – whether it be as serious as Zerpa’s, or more mundane.

“We would start the investigation by alerting [the district]. We start talking to the victim or the victim’s parents immediately.”

To give the accused due process, the investigation must involve the teacher against whom the accusation is made. “Whether that’s an instructional complaint or abuse or harassment complaint, the teacher has a right to a union representative, and must receive a chance to tell their side of the story,” Chapman said.

“We work with [the district] to decide if there’s need to put someone on paid leave while the investigation happens. If there is going to be opportunity for continued harm to students, [the teacher might be placed on leave].”

The Portland Association of Teachers is heavily involved in the process.

Maggie Raczek, a biology teacher and Lincoln teachers’ union representative, said that the union has an interest in both keeping students safe and ensuring accused teachers have due process.

“If you are an active member of the union, you are provided with an attorney to help you through the process. It’s all about due process rights, not guilt or innocence,” she said.

Jenkins declined to comment to the Cardinal Times, citing a non-disclosure agreement she signed with the district.

According to the TSPC investigation, Jenkins denied sharing information about her personal life, kissing Zerpa and sending the student a love poem. She admitted to the trip into the tunnels and that her chat messages with Zerpa “crossed the boundary.”

Zerpa was satisfied with the investigation process in his case – the speed, thoroughness and supportiveness.

“Overall, the Lincoln community, especially administrators, were there for me,” he said. “Ms. Chapman had a lot of things on her schedule for the day, but as soon as she opened up the folder [with the evidence], she cleared the rest of her schedule.”

That same day, Zerpa said, he met with administrators, lawyers, police officers and district officials.

The next day, when Jenkins arrived at work, she was met by police detectives, according to Zerpa.

Jenkins had already planned to leave Lincoln that summer for Cleveland High School, but was fired by the district, according to the TSPC. She eventually also lost her teaching license after a follow-up investigation by the TSPC, which licenses teachers.

Though Zerpa said he was satisfied with the investigation process, he knows it never would have even been initiated if not for his mother.

“If it hadn’t been for my mom being a mom, I think I would have pretended it didn’t happen and repressed it in my memory,” he said. “I wanted to sit back and let it disappear. That would have let [Jenkins] just go do the same thing with another kid.”

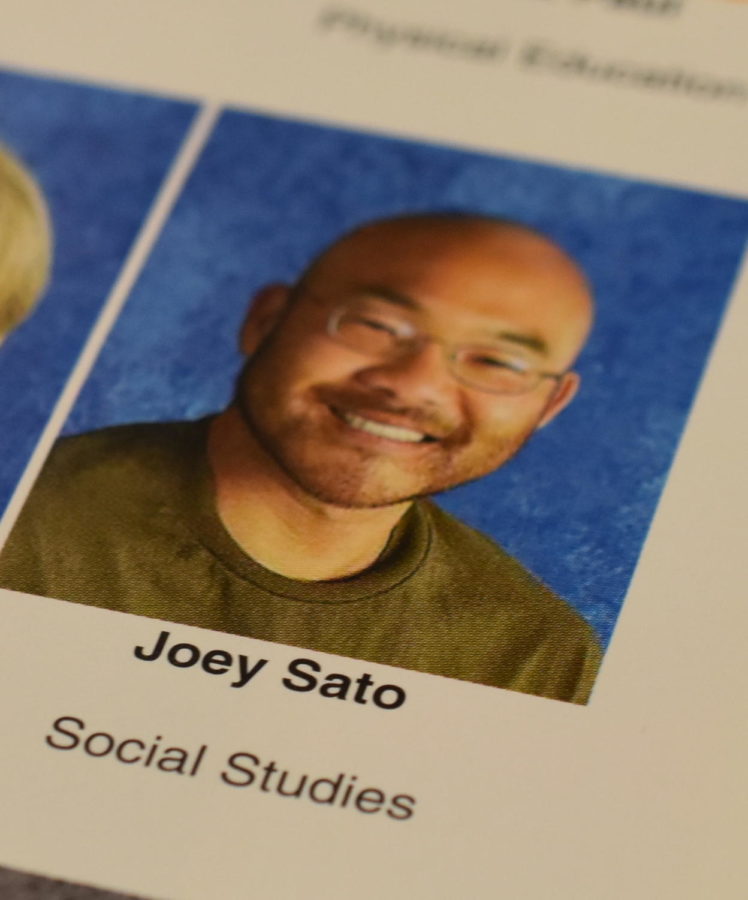

A case with similarities to Jenkins’ occurred at Lincoln just a few years later, this time involving social studies teacher Joey Sato.

In 2012, according to a TSPC investigation, at least three female students – from freshmen to seniors – came forward about Sato. Two said they were spoken to inappropriately and one said she was kissed by the teacher, who was 44 at the time.

Sato reportedly also asked girls for their phone numbers and friended them on Facebook so that he could meet them on weekends, the TSPC investigator found.

Another 12 students confirmed these accounts to Principal Chapman, the TSPC investigation report said.

Sato resigned in 2013 at the conclusion of the school’s investigation. TSPC later revoked his teaching license.

When contacted by the Cardinal Times, Sato declined to comment, citing confidentiality agreements with the district.

In an interview with TSPC investigators, Sato “admitted that in hindsight he had boundary issues,” according to the report, but denied “any romantic or sexual intentions toward any student ever.”

Both the Sato and Jenkins cases raise questions about what Lincoln does to encourage early reporting of complaints. In both cases, the misconduct went unreported for weeks or months.

Why students don’t report

Christine Jenkins pictured in the 2008-09 yearbook. Jenkins was accused of pursuing a relationship with a freshman that year.

The first obstacle victims face in reporting misbehavior is deciding who to go to. The Cardinal Times found that when asked about this, many current students did not have an immediate answer and had to think it through.

A common initial response was parents, who could then help report to school administrators. But as junior Jessica Motley acknowledged, “not everyone is in the situation at home where they can tell this type of thing to their parents.”

Another possibility mentioned by students was to go to counselors and administrators.

“It takes initiative to come up with [an answer] that should be intuitive,” said junior Josh Gregory, referring to the decision about who to report to. He said this was especially worrying given that victims in this situation may have strong emotions clouding judgement.

But even when a victim does know who to report to, a litany of other factors can hold him or her back.

The power dynamic between students and teachers is a major reason students are disinclined to report abuse, said English teacher Amanda Jane-Elliott. The student may feel less empowered to speak up because the teacher is in a position of authority, she said. A student might be worried about how her or his grades could be impacted.

The fear of repercussions is also a deterrent. In today’s digital world, it is much easier for news, such as the report of misconduct by a teacher, to spread among students, said Elliott. “The minute something happens, it’s on social media, and everyone knows,” she said.

This fear may stop some victims from reporting. “I can’t imagine anything more difficult than coming to school when everyone is talking about what happened to you,” said another teacher who agreed to speak on condition of anonymity.

This fear is backed up by medical studies. Sarah Dobey is a licensed professional counselor and clinical director at the Integrative Trauma Treatment Center in Northwest Portland. She has worked with victims of sexual abuse and knows the many difficulties victims face in coming forward.

“There’s a lot of neuroscience that shows that in [reporting] situations, our amygdala (which controls fear) is activated and parts of the brain that control speech shut off,” Dobey said.

Another factor that influences whether students report is that sometimes they don’t recognize that the teacher’s behavior crosses the line into sexual misconduct.

“As a 15-year-old kid, I thought I was mature and aware enough to recognize [Jenkins’ behavior] for what it was, but it took a long time,” Zerpa said.

Though not speaking on Jenkins’ case, Elliott says that this difficulty in recognizing the behavior can be a major issue. “Even if the student thinks it’s a ‘real relationship,’ it’s not, because the power dynamic is wrong. This [justification of the behavior] not only makes it harder to report it, but even to see it’s a problem.”

Elliott said this might be exacerbated if a teacher is particularly popular or charismatic or lax about rules, such as allowing cell-phone use in class. This attitude already begins to erode some of the boundaries between students and teachers.

Principal Chapman said she saw this first hand when working in a battered women’s shelter in Washington, D.C.

“I really learned to never underestimate the power of an abusive person because it crosses all gender, racial, socioeconomic classes. A 16-year-old might not even know it’s happening. That’s the power of grooming, especially when you’re in a trusted relationship with a coach, a teacher, a priest.”

Zerpa feels that grooming may have happened in his case, and others. He said Jenkins was very well-liked by a significant portion of students and fellow teachers.

Students would often be in her room during break times and after school talking with her about non-school-related personal problems, according to Zerpa and other Lincoln alumni who were in Jenkins’ classes.

This non-academic relationship can erode the natural boundary between a teacher in his or her professional role, said Zerpa.

“If you have a ‘cooler,’ ‘hipper’ teacher that doesn’t stick to the status quo, it breaks down that barrier between teachers and students a little bit, and you start seeing them more in a ‘cool adult’ role,” he said. “So when they start doing things wrong, you start to justify that behavior.”

The 2012 case involving Sato, the social studies teacher, follows the same pattern.

One former student of Sato’s, Alex Meyer, told the Cardinal Times that the teacher fostered close relationships to students.

“He was particularly friendly with female students. He took a liking to them just as they took a liking to his charm,” said Meyer, who had Sato in 2011-12. “He was much closer with some female students than other teachers were.”

Another case of misconduct involving a charismatic educator at Lincoln occurred in May 2014, when substitute teacher Daniel Dickason filled in for a history class.

Dickason, who was 64 at the time, quickly broke down the professional barriers meant to separate teachers and students, a TSPC investigation obtained through a public records request found. He showed students his Facebook feed, which included photos of his high school prom date, a marijuana leaf and a “provocative pose with a tango dancer,” according to the TSPC.

He also allowed students to be on their phones and go to Starbucks during the class, the report said.

After developing this relaxed attitude with students, he passed one female student a note asking her to attend his birthday party that weekend, investigators found. The student felt extremely uncomfortable and reported Dickason to the administration.

He resigned as a substitute in 2014 as part of a settlement agreement with the district.

Dickason could not be reached for comment.

In his interview with the TSPC, Dickason admitted he “violated student-teacher boundaries and used poor judgment” during a time when he was “suffering from clinical depression and had an increasing problem with alcohol,” investigators wrote. He denied any romantic or sexual interest in the student.

Another consequence of raising concerns about a popular teacher: reporting can create repercussions for the student, said Elliott.

“You wouldn’t want to be the person who goes against the crowd. When you go against the crowd, you’ve upset the teacher’s life, people aren’t going to believe you and you’ll be called names – it’s a lose-lose situation.”

This was a factor in Zerpa’s case, he said.

“I basically disappeared all summer because I could not stand the messages I was getting,” he said. “Given how popular of a teacher Jenkins was, she had almost a cult following. Because she had awesome relationships with so many students who loved her, she turned to those people to make it look like I was coming out of left field with all of this.”

But the retribution against Zerpa went even further: He said he felt repercussions from other teachers for his remaining three years at the school.

“The teachers were split between ‘Team Jenkins’ and not, and I could feel which teachers still had a grudge against me. They knew, ‘this is the kid who got our friend fired.’”

Another source who requested to remain anonymous confirmed that Zerpa was treated poorly by other teachers who supported Jenkins.

Reducing stigma around reporting

Joey Sato pictured in the 2011-12 yearbook. Sato was the subject of several sexual misconduct complaints that year.

What can be done by the school to clarify steps to take and reduce the stigma around reporting? The Cardinal Times fielded suggestions from people across the Lincoln community.

First, many said, the school needs to make clear the people to whom victims can report.

Jeff Edmundson, a former Lincoln teacher and current Constitution Team coach, proposed that this education on resources occur in conversations with counselors or at an assembly. “If you want to set the bar, it has to be verbal and direct, not some handbook that no one reads.”

However, in doing this, Edmundson warned, the school needs to make sure it is not put off as another “pro forma” message from the administration. “When you keep reminding people, they tune out,” he said.

He said he is not sure how to make the message stick.

It could be done through “a page in the planner where it is laid out, or posters,” suggested Elliott, the English teacher.

A common theme throughout the suggestions was to educate students on what behaviors cross the line – reducing the problem of students justifying teachers’ behavior.

“We need to be more explicit about the types of situations in which [students] should [report], and name it,” said Raczek, the biology teacher. She suggested perhaps folding this lesson into existing anti-bullying presentations.

Another teacher, who requested to remain anonymous, said that the school should let students know what the boundaries are and what behaviors cross the line.

The teacher suggested that this be weaved into the curriculum in health classes, which are required. “Kids are just discovering themselves as sexual creatures, so these are questions that are always on the mind – ‘am I reading too much into this, or not enough?’” the teacher said.

To reduce the stigma around “snitching,” Elliott suggests students need to work together to create a more supportive environment for those who report.

“Student activists could create a culture where students feel empowered to call things out. Students need to let each other know that they won’t be horrible to someone who says something,” Elliott said.

There is also the fear of not being believed by administrators, but Chapman, the principal, said that awareness of the investigation procedures can alleviate this fear.

Due to employer-employee confidentiality laws, Chapman said she is unable to inform the student about the result of an investigation initiated by a complaint. This may have fostered a belief among students who have reported that the administration does nothing.

“[A person who makes a complaint] may feel like ‘I have told [Ms. Chapman] this’ and nothing happened. [But] something happens when somebody comes and shares that information, but it may not be that the person was fired.

“It may be that there was a letter of expectations (which suggests ways to avoid misbehaviors by the teacher), it may be that there was a conversation, it may be that there was documentation,” she said.

Zerpa said he was contacted throughout the summer following his complaint as PPS conducted its investigation, but he was not informed of the eventual outcome of his case.

Though Chapman could not speak specifically on Zerpa’s case, the confidentiality laws likely are why Zerpa was never informed of the official outcome of his complaint.

Another obstacle is the fear of repercussions from the accused teacher. Raczek, Lincoln’s union representative, hopes that a revision in the new teachers’ contact adopted in February could alleviate one concern.

Article 25, which addresses complaints against teachers, formerly read, “If a complaint is made to a supervisor about the professional educator […] the supervisor will request that the complainant discuss the matter directly with the professional educator.”

This would have forced student victims to directly confront their abuser.

The new contract adds to the end of that sentence, “except if the complaint involves allegations of sexual conduct.”

Raczek said this is something the union strongly pushed for. “We don’t want the student having to go to talk to the teacher about this,” she said

Dobey, the trauma counselor, said that to encourage reporting, there first needs to be a focus on mental health in the education system.

“Coping skills, stress tolerance, emotional regulation all need to be integrated into the curriculum, and we need to have more professionals working in schools,” beyond counselors who have massive caseloads and a focus on college admissions, she said. Doing this will help a student cope with the trauma of sexual abuse and encourage them to come forward.

“Any sort of abuse can be very alienating,” she said.

A former Lincoln counselor, Joyce Liljeholm, said counselors’ workloads make them more impersonal to students. “As a counselor, I was concerned about students being able to speak privately with me, as our case loads were over 400 students,” she said in an email.

Chapman said that two new staff members hired with Measure 98 funds could alleviate this problem.

One of them is Judy Herzberg, a mental support counselor who will be in the counseling center 10 hours per week.

“My role is to work with students and families on emotional and mental health concerns,” Herzberg said. She receives referrals from counselors and can work with students for free and without parent consent or knowledge.

She said that as a PPS employee, she does have a mandatory duty to report abuse against a student, but all other discussions are confidential.

In the case of sexual misconduct by a teacher, she said she would talk with the student and “help them understand that it is not their fault.”

Further, newly hired student engagement coach Michelle Hardaway will help monitor attendance, which can start to decline when the student is targeted by a teacher, Chapman said.

Herzberg and Hardaway supplement the work of Gina Batliner, a licensed professional counselor who works for Western Psychological and Counseling Services, but has an office in the counseling center at Lincoln.

Batliner does bill students who come to her, so she more often works with students who have talked to parents beforehand.

Dobey, the counselor at Integrative Trauma Treatment Center, also said that the professionals and administrators who are asking students to report to them need be proactive and make themselves known on a personal level – not just a name on a poster or in an announcement.

“[Victims] need to know the person on the other end (of a report) will be kind and compassionate. Having more practitioners come into classrooms and talk about who to go to will give a face [to these resources].”

Zerpa agreed. He said he was glad that he already had a relationship with administrators. “It made it easier for me because I didn’t feel like I was telling a complete stranger what happened.”

Former teacher Bart Millar proposes that teachers be required to keep the windows on their doors unobscured to protect students during one-on-one meetings.

Proactive ‘vigilance’

However, the best situation would be if the abuse never occurred in the first place, said Chapman.

One of the best prevention strategies is required yearly online training for teachers that includes setting clear “boundaries” with students, she said.

This training was implemented three years ago to complement existing annual training on teachers’ mandatory reporting requirements when they spot evidence of child abuse.

Examples of aspects of the boundary training are how teachers respond to students who ask for a hug, to managing social media interactions with students and never giving rides to students, Chapman said.

According to the TSPC investigation, Jenkins broke two of these boundaries by hugging Zerpa and messaging him on social media.

Edmundson, the former Lincoln teacher, also worked as director of teacher education programs at the University of Oregon until 2015. One of the lessons he spent “quite a bit of time on” with teachers-in-training was how to maintain clear boundaries.

“Lincoln does a good job finding teachers who want to connect with students,” said Edmundson. “The danger in that is signals can get read wrong. You don’t want to have anything that could be misinterpreted.”

Another recommendation that Lincoln makes through its training, but does not require, is to keep classroom doors open while meeting one-and-one with students, said Chapman.

She said it could be an official policy, but it would not have prevented the misconduct in the cases she investigated.

Zerpa said that Jenkins did not keep her door open during all of their meetings, and thinks it could help prevent misconduct. However, he did point out that many of his meetings with Jenkins stretched late into the evening, when the halls are mostly empty anyway.

Former Lincoln teacher Bart Millar took the door idea further, suggesting that teachers should also keep the window in classroom doors uncovered at all times.

A recent check by the Cardinal Times found that 22 of Lincoln’s 65 classrooms have obscured windows. Three classrooms have no window in the door.

However, the most vital way to prevent sexual misconduct is vigilance, Chapman said.

“Some of it is empowering and training students to speak up and the other side is everybody being on the lookout for that manipulative powerful personality,” she said. “In lots of cases we’ve read about, in hindsight, there were usually red flags.”

Chapman and Edmundson noted that some teachers have an aversion to reporting on their colleagues.

“Things that might have disciplinary potential, teachers leave that to administrators. It’s not teachers’ job to get in the way of what other teachers do in the classroom, both about boundary issues and just teaching quality,” Edmundson said.

“It’s partly bred by the union contract,” he said. “Union tradition [in Portland [has been] that teachers shouldn’t be involved in disciplining other teachers.” He said this is something he critiqued when he was on the Executive Board of the Portland Association of Teachers (PAT) in the 1990s.

Suzanne Cohen, current president of the union, said that the idea “saddens me.”

“It absolutely is not the case,” she said. “The PAT is not to be blamed for district failures” in investigating teachers, she added.

Chapman said she has noticed a shift in the attitude of teachers during the course of her career.

“Even when I was a teacher 15 years ago, teachers had this belief that, ‘Oh, that’s the admins’ job. Even if there’s bad teaching next door, that’s really not anything for me to comment on,’” she said. “But we hire now for collaboration and peer feedback [between educators].” This could include feedback on inappropriate behavior, she said.

Warning signs in hiring

Throughout the course of their investigation in the Jenkins case, the TSPC discovered facts that raise questions about whether PPS and Lincoln are doing enough to vet hirees.

In child support court filings, the commission found that Jenkins had had a child with a 16-year-old boy in 1992. Jenkins was 27 at the time, the investigation found. The Cardinal Times was able to locate the same records with an online search.

“[Jenkins’ actions in 1992] call into question her suitability to teach adolescent males,” wrote Erin Olson, Zerpa’s attorney during the investigation, according to records obtained through a public records request. At the time when Jenkins worked with Zerpa, he was just 15 years old.

Olson declined to comment further when contacted by the Cardinal Times.

While these court records may not have been digitized at the time of Jenkins’ hiring, they were always available at the courthouse and could have been part of a background check.

“[This] showed it wasn’t the first time she had groomed a child,” Zerpa said.

Jenkins told TSPC investigators she did not know that the father of her child was 16, according to records of the interview. She said she believed the father was 20.

Elisa Schorr, Title XI coordinator in the HR department at PPS, explained the background check process for new hires.

“The TSPC does the fingerprint check and fitness for duty investigations on any licensed position. [Then] our security services does a criminal records check by name, date, and social security number,” she said in an email. “We look at convictions, arrests and court orders, such as restraining orders. We have access to court records in case we need more information.”

On why Jenkins’s actions in 1992 did not raise red flags, PPS spokesman David Northfield stated, “Since it was not a criminal matter, it would not show up in a background check.”

Not referencing the Jenkins case specifically, Chapman said the vetting process for new hires has improved in recent years.

“The background checks are much more in-depth and sophisticated, even in the last five years,” she said.

Chapman also said the background check now has the mandatory step of contacting the teacher’s last direct supervisor, even if it is in another state.

The Lincoln administration relies on the school district to vet new teachers, she said.

“We interview from a pool of candidates that [the district] pre-screen[s] and then we send HR the name of our first choice and we do reference checks,” Chapman said. “We don’t hire, we just get to recommend for hire. Then HR completes the rest of the hiring process after a full background check.”

Whitehurst was allowed to move schools after complaints by students. When he arrived at a new school, his personnel file seemed to be cleared of the reports against him, according to The Oregonian.

The Whitehurst case has led to calls for better inter-school communication about potential hires.

Chapman said this is already happening to an extent.

She is now required to communicate any sexual misconduct complaints to a senior director at the district. Before, any notes on the teacher that didn’t result in discipline, but were taken for documentation purposes, would only go into the teacher’s “building file,” which contains records of complaints that stay at Lincoln. Now, the district has these files, as well.

“PPS has responded to recent issues and set up new practices so more information goes to the central office, and that is a good improvement,” Chapman said.

Further, she said, “principals work together to protect students and no one I know would move a teacher they thought was potentially harmful to students, to another school.”

Lincoln campus security officer Frank Acosta believes positive change will result from the investigation into what went wrong in the Whitehurst case.

He is sometimes involved in investigating reports of misconduct, and he said requiring an even bigger paper trail in these investigations could help ensure that reports are not ignored or misplaced when teachers move schools.

This office in the counseling center is home to two mental health support professionals, Gina Batliner and Judy Herzberg. They are resources for students who experience sexual misconduct by teachers.

‘Come talk to me’

New superintendent Guadalupe Guerrero, who came to PPS in October, said he is committed to preventing sexual misconduct by teachers district-wide.

“I have no tolerance for the [mis]behavior of the adults who parents are trusting their kids’ safety to,” he said at a press conference with PPS school newspapers in December.

“We need to have a really good process for investigating any concerns. When we hear about it, we should go about it in a very assertive way. We need to respect the employee’s due process, but some [complaints] are immediately elevated [to the district level].”

Several interviewees for this story brought up the increased attention nationally on sexual harassment as a reason why student victims should feel supported in coming forward.

“I hope the ‘MeToo’ movement will encourage more people to be vocal about their experiences,” said Dobey, the trauma counselor.

But no matter what changes happen on the district level or nationally, Chapman said her door will always be open.

“If anyone feels unsafe at Lincoln, come talk to [me],” she said. “If you don’t feel safe coming alone, you can bring your parent or a friend.”

The vice principals will always be there, as well, she said. For those concerned with confidentiality, the school nurse, Mary Johnson, is bound by additional privacy laws as a medical professional.

In addition, students can make anonymous tips to the SafeOregon website and tip line, which end up in the hands of Lincoln administrators.

“I lose sleep until it’s resolved and so it becomes the top priority,” said Chapman. “I always feel responsible as the principal that this could happen under my watch, even if I didn’t know about it or couldn’t have known about it. Once I do know about it, I really need it to be addressed. And I really feel responsible.

“[Students] just should never have had to deal with anything, in school, like that.” •

Resources

Who to talk to if you see or experience misconduct

If you are in immediate danger, call 911.

At Lincoln

Note: PPS employees are mandatory reporters, meaning that they must report evidence of abuse to authorities.

- Lincoln administrators: Peyton Chapman ([email protected]), Sean Mailey ([email protected]), Alfredo Quintero ([email protected]), Ginger Taylor ([email protected])

- Counseling Center: Jim Hanson, Gina Batliner, Judy Herzberg (speak to your counselor for a referral)

- Room 126: Mary Johnson, school nurse ([email protected])

- SafeOregon tip line (anonymous tips will be passed to Lincoln administrators): Call or text: 844-472-3367, Email: [email protected], Mobile app: SafeOregon on iOS/Android, Website: http://safeoregon.com/report-a-tip/

- SAFER Club: Instagram @safer.lhs, Email [email protected], Student leaders (not mandatory reporters): Lea Kapur, Paige Lutz, Maggie Satchwell, Tori Siegel, Julia Ziegler

*******

Local support

- Multnomah County Victims’ Assistance Program: 24-hour on-call response to the victims of sexual assault (503-988-3222)

- Sexual Assault Resource Center (SARC), based in Washington County: 24-hour anonymous, confidential, and free support (503-640-5311)

- Victim Rights Law Center (VRLC): Se habla español (503-274-5477)

- Call to Safety: Call the crisis line 24/7. Always free and confidential. (503-235-5333)

*******

National organizations

- National Sexual Assault Hotline: 1.800.656.HOPE (4673), Live chat: https://www.rainn.org/

- Safe Horizon: Need help? Call our 24-hour hotline (1-800-621-4673)

- Teen Line (Teens Helping Teens): Call 310-855-4673, text TEEN to 839863

*********

Compiled by the Cardinal Times in collaboration with Integrative Trauma Treatment Center and Lincoln’s SAFER (Students Active For Ending Rape) club.

Esther Warkov • Apr 3, 2018 at 12:50 pm

Congratulations on your groundbreaking exemplary work. You might want to check out the resources from Stop Sexual Assault in Schools, a national nonprofit based in Portland. http://stopsexualassaultinschools.org. The free video (with Action Guide) Sexual Harassment: Not in Our School! was created with Portland students. http://stopsexualassaultinschools.org/video/ To collaborate, contact [email protected]. #MeTooK12

Anon • Apr 2, 2018 at 11:49 pm

Good job with the article.

Anita • Apr 2, 2018 at 5:38 pm

Well written and thorough coverage of the topic! Well done Jamie and team!