How Lincoln Celebrated Black History Month

By Skylar DeBose and Leela Moreno

Posters on lockers, conversations in class and a memorial in the main hall, all in celebration of Black History Month. Black History Month (BHM) is a time when black history and lives are celebrated.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the original celebration of black history was the second week of February, chosen to line up with the birthdays of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln, but in 1976, it expanded to the whole month.

Black History Month is a widely acknowledged celebration, but educators have different perspectives about observing it.

“You can’t teach Black History Month, you can acknowledge it,” said Vice Principal and Brothers of Color mentor James McGee.

During the month, students were immersed in black culture and history, acknowledging all sides of American history. Critical Race students put up posters on lockers, educating others on the life of Trayvon Martin, black activists and the Black Lives Matter Movement.

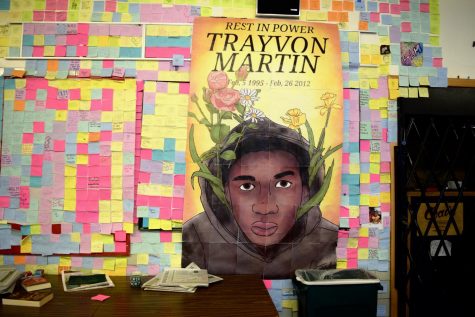

Critical Race students came into freshman English classes to educate students on the Black Lives Matter Movement. In the main hallway the same students created a memorial for Trayvon Martin, a seventeen year old black boy who was shot and killed. Surrounding the memorial were sticky notes where students expressed their feelings about his ongoing impact on their lives.

Jessica Mallare-Best has been teaching at Lincoln for five years and is the teacher who created the Critical Race program.

Along with teaching Critical Race, Best teaches Modern World History, where she brings in education about race and racism.

“I firmly believe it’s something that should be embedded in every subject, every school, every age group,” said Best.

Her ideas resonate with her students.

Emily Cigarroa, a senior who has taken two years of Critical Race finds the class meaningful.

“Critical Race Studies is one of the few spaces I have experienced in which we have talked about black history during Black History Month, but also all year round.”

“I wasn’t taught about black history in middle school,”said freshman Zack Andoh. He went on to say that younger kids can be more aware of black history.

Since middle school, Andoh said his learning experience has dramatically improved. He said that a key part of that improvement was the US History Ethnic Studies course.

Ethnic Studies is a class that all freshmen at Lincoln are required to take. Students have noticed that instead of focusing on the traditional white history, this class teaches from a different perspective. They are taught about the history of people of color, women and members of the LGBTQ community.

Andoh is a member of Brothers of Color which he describes as a safe space. Having black educators such as McGee has, “made it easier for people of color to approach.”

“Often you’re the only one in the classroom that looks like you,” said McGee.

Because of this McGee said that reaching out to the few students of color at Lincoln is something that he takes seriously.

Many students and teachers, including Best, McGee, Andoh, and Cigarroa, believe that though Lincoln makes an effort on educating others about Black History Month, they could be doing more year round in order to fully educate others on black history.

Cigarroa thinks that Lincoln needs more all-school celebration of the month in order to fully celebrate black history. She believes that BHM should not only be an in-class event and said that we need “more full school acknowledgement of Black History Month.”

Both Andoh and McGee strongly believe that Lincoln needs more teachers and administrators of color.

When asked what McGee would like to see more of, he answered with, “We need more people of color in higher [positions],” and continues with, “I recognize some of the challenges with that.”

“I can empathize with the whole thing about how black kids would want more black educators,” said freshman Srishti Bakshi. Though Bakshi identifies as Indian and not black, she feels much more represented when she sees people that look like her in positions of power.

Students and faculty of all races unite with a common request. They believe that in order to have a strong black history education, Lincoln needs people of color in higher positions.